|

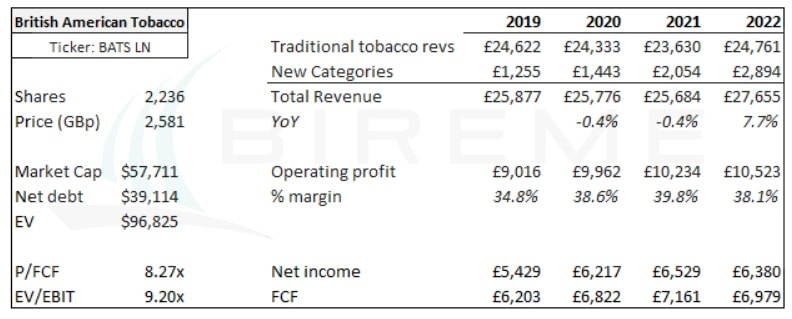

We recently invested in British American Tobacco (BAT).

BAT, formed in 1902, is a global tobacco company with a strong position in next-generation products. Despite its growing profits BAT's valuation has dwindled to just 8x FCF. At these levels we think BAT offers a compelling investment opportunity. Introduction

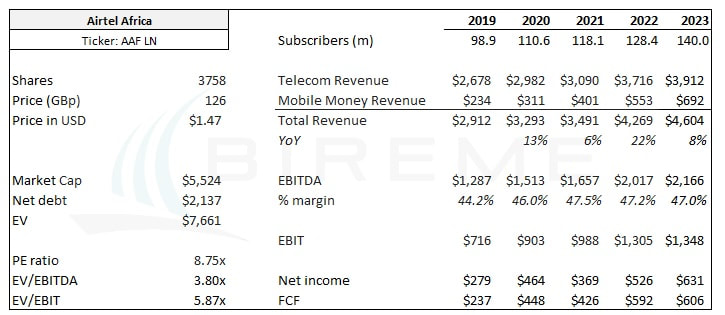

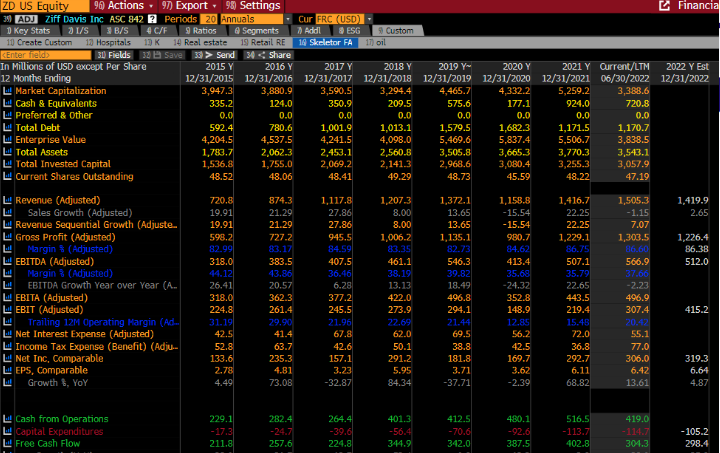

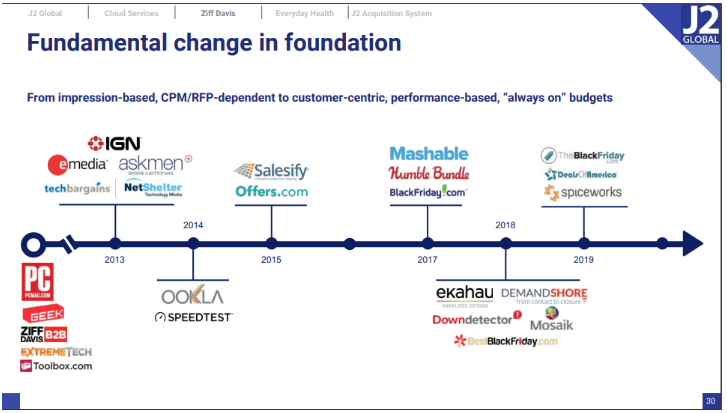

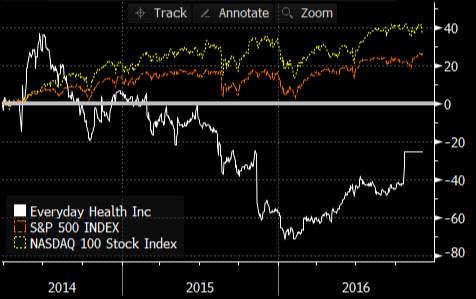

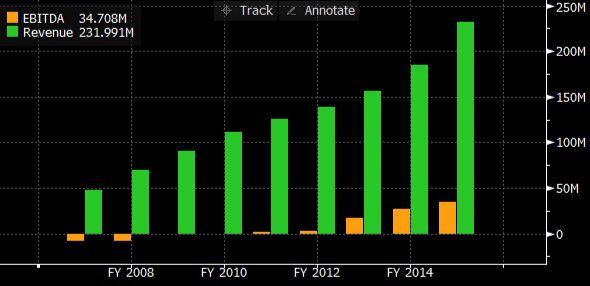

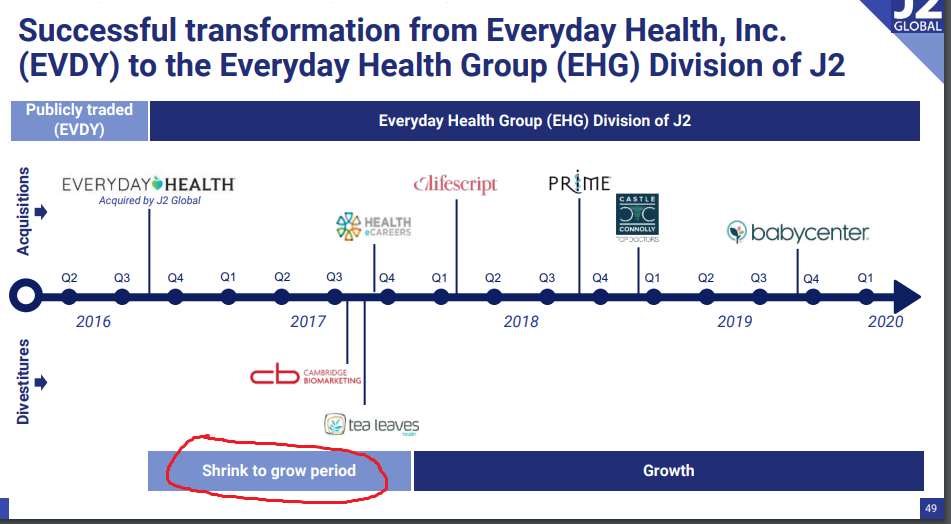

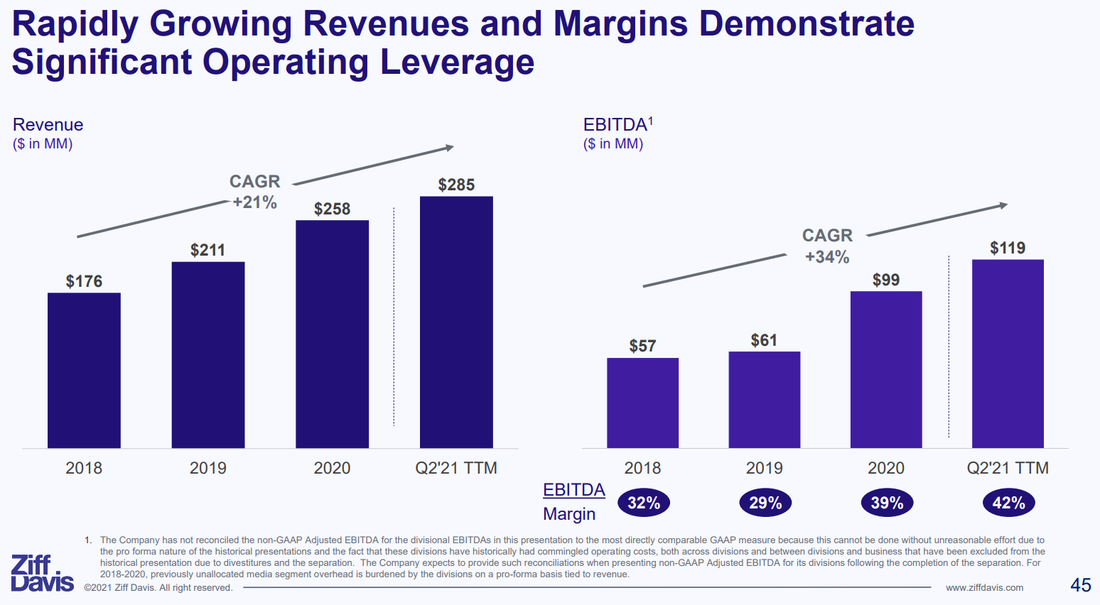

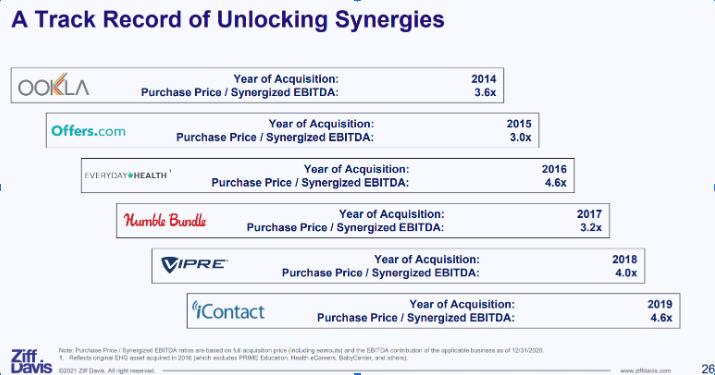

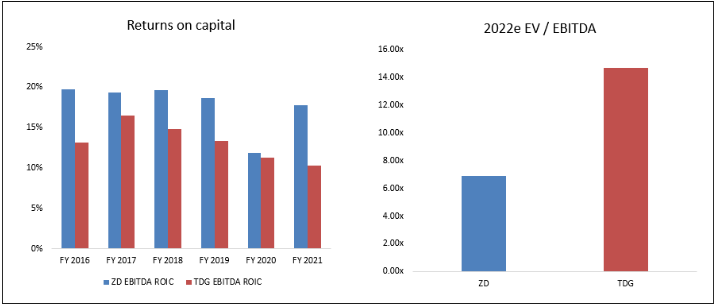

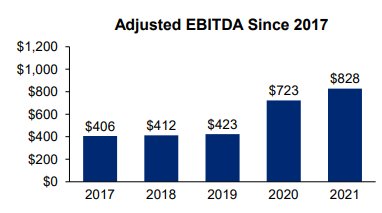

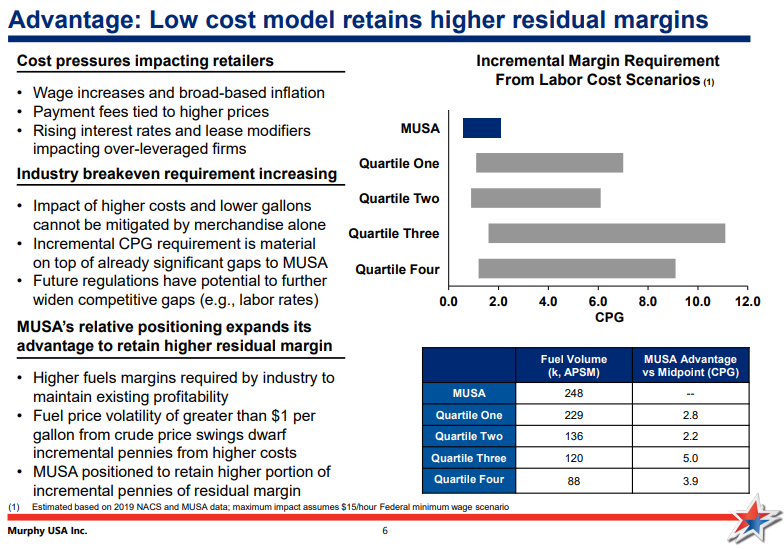

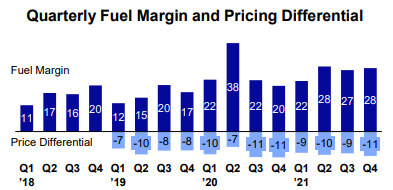

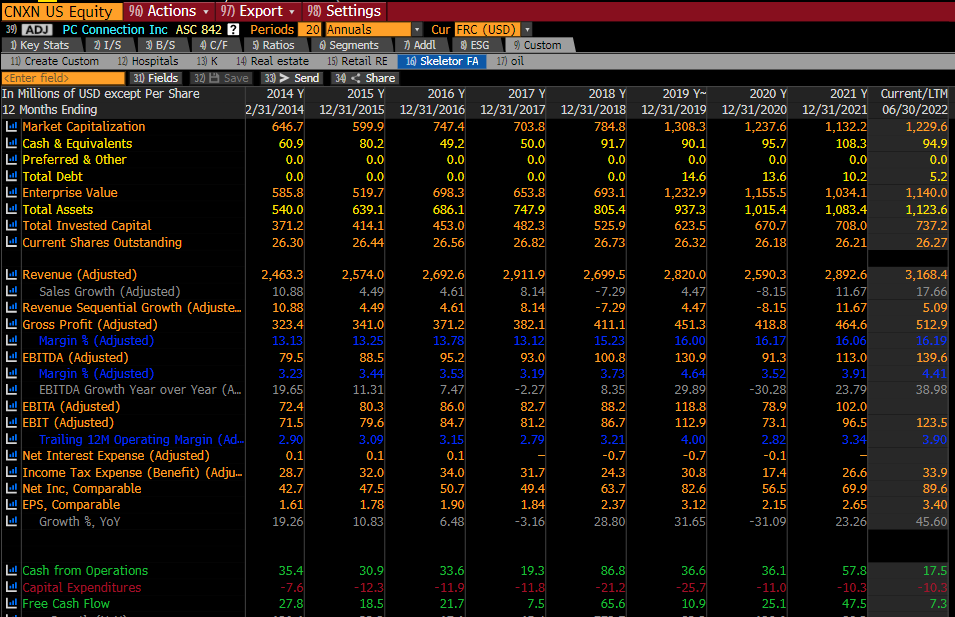

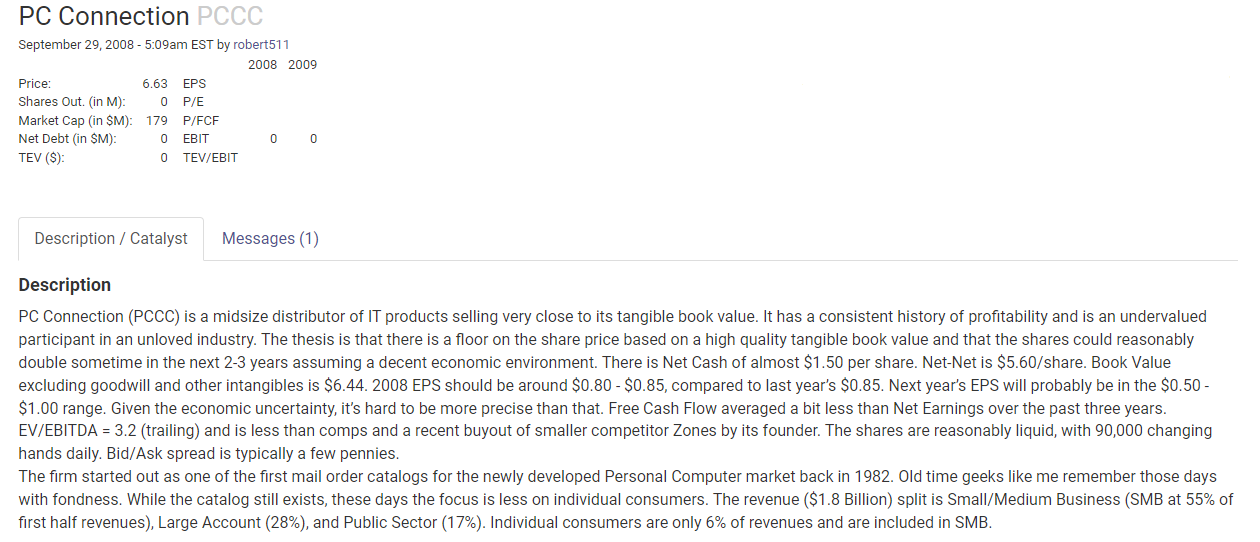

Airtel Africa is a profitable, high growth, yet very cheap telecom business operating in Sub-Saharan Africa. At a market cap of about $5.5b USD, the price-to-earnings ratio is less than 9x. On an EV basis, the company trades at just 6x EBIT. This valuation gives the company no credit for the tremendous historical growth and potential growth runway. Since 2017, revenue has grown by two thirds, from $2.8b to $4.6b, and EBITDA has more than doubled $2.1b. Ever heard of a company called J2 Global? I thought not. Originally, J2 Global was a company that sold fax-to-email subscription software. Over the years it took the profits from the subscription business – about $150-200m per year – and bought underperforming websites. They eventually built up a base of about $1b of non-fax revenues before separating into two publicly traded companies. Today the fax business is called Consensus Cloud Solutions (CCSI), and has a $950m market cap. Ziff Davis (ZD), the websites, are what’s left. The stock is down almost 50% since Nov 2021 and trades at a market value of about $3.4b. This comes to about 11x earnings and less than 7x this year’s EBITDA. This is quite a modest valuation for a firm that has grown revenues at its stable of websites 6x since 2014 (results below include the jettisoned fax business). The properties at ZD are IGN, Mashable, Ookla, PCMag, DownDetector, Everyday Health, and others. Below is a timeline of some of their key acquisitions from the JCOM 2020 Investor Day: The Mashable acquisition is instructive as to how Ziff Davis operates. Mashable was valued at $250m in 2016, but ZD managed to buy it for just $50m the next year. So ZD got an 80% discount vs the prior year’s valuation. The purchase was about 1x revenues, according to estimates seen by Variety. Today Mashable probably generates $50-75m in annual revenue according to estimates by similarweb.com. So slightly more than when it was purchased. But ZD operates with ruthless efficiency: the company has 35% adjusted EBITDA margins. This implies that today Mashable could be doing $20-25m of EBITDA. At a 10x valuation, this implies that ZD has generated a 4-5x return on its initial investment. I consider these estimates fairly conservative. Another notable purchase was the website everydayhealth.com, which Ziff Davis bought in 2016 for $465m. Like the Mashable deal, this was also a substantial discount to previous valuations. After going public in March 2014, EVDY had traded down more than 40% by October of 2016. It trailed the market substantially, with the S&P 500 up 26% and the Nasdaq up 39% over that time frame. This was not due to poor financial performance as far as I can tell. As of Q3 2016, EVDY had grown revenues 9% on a T12 basis and grew revenue 29%, 21% and 10% in the preceding years. Margins were decent too, with EBITDA margins clocking in at 11.9%. Perhaps initial expectations at the IPO were simply too high. ZD’s acquisition of the site was at 15x trailing EBITDA, but this is not the full story. ZD slashed costs, putting the segment into a “shrink to grow” period. This drove revenue below $200m. From the 2020 J2 Global analyst day: These cuts, while shrinking revenue, resulted in dramatically increased profitability. Meanwhile, ZD bolted on smaller acquisitions like BabyCenter. Today, the Health Group at ZD now has around 100m monthly unique visitors and is one of the largest contributors to ZD results with ~$120m of EBITDA. Deals like Mashable and Everyday Health seem to demonstrate ZD's prowess in acquiring these underperforming and low-profitability websites. This strategy has few publicly traded competitors. But despite the uniqueness of their strategy, we see no reason why it can't be successful, In fact, it strikes us as a little bit similar to what Constellation Software does in niche SaaS or Transdigm does in airplane parts. One advantage ZD has is that it appears there is not much competition in acquiring these assets. ZD claims they have averaged purchases at 5x EBITDA and highlights a number of deals that were even cheaper than that on a fully-synergized basis: You should never trust a company with data like this, because they could be cherry picking. Cheap acquisitions must show up in the final numbers. In ZD’s case, the consolidated financial statements show that 5x EBITDA is a reasonable estimate. If we exclude cash of around $750m, total operating assets at ZD are $2.75b essentially all of which was acquired. This figure is about 5.2x expected EBITDA for this year. In other words, EBITDA returns on invested capital are around 20%. While this can’t compare to Constellation’s near 50% EBITDA ROIC, it compares quite well against Transdigm’s ~15% EBITDA returns. Despite better returns on capital, ZD trades at half the EBITDA multiple of TDG. We are sticking ZD on our watchlist and will be following it closely going forward. If you saw my post from last week, you’ll know that I have decided to study at least one new company every day and post on it. I’m a little behind already, but today’s second post looks at Murphy USA (ticker MUSA). Murphy USA runs gas stations, and had about 1700 locations at YE 2021. They were a 2012 spinoff from Murphy Oil, a $10b enterprise value oil producer based in Houston. At the time of the spinoff, the firm listed the following “competitive strengths” “Strategic relationship with Walmart'': Roughly 1000 of their locations are located adjacent to Walmart, which drives significant traffic for MUSA. They collaborate with Walmart on a fuel discount program. “Cheap gas prices”: Their business is built around efficiency, high traffic, high volumes, and low prices. They are also a leader in low-priced tobacco products. “Low-cost operating model”: MUSA’s small-footprint stores, with a focus on fuel sales, drive low capital and maintenance costs. Only one or two attendants need to be present during business hours. Also, they own their locations so do not incur rent expense. “Advantaged fuel supply”: MUSA claims to source fuel “at or below industry benchmark pricing”. I’m not sure how much I believe this is a real advantage relative to peers. At the time of the spin, the company did about $300m of EBITDA at just under 1200 locations. Their footprint has grown relatively slowly, building stores both adjacent to and independent from Walmart locations. In 2019, the final pre-COVID year, the company did $435m of EBITDA out of 1500 units. The Walmart agreement ended a few years back, and now they are focused on freestanding locations for growth. The valuation is tricky. On 2022e earnings, the stock looks cheap at about 11x PE. The problem is that earnings are at a cyclical peak, having ballooned from $160m in 2019 to $570m for 2022e. Below are the adjusted EBITDA figures they present in their most recent investor deck. Did anything fundamentally change in this business to create this hockey stick in earnings? Or is this ephemeral? In most cases, margins distributing pure commodities, like gasoline, should be cyclical. The company argues that fuel margins are “expected to settle at a higher equilibrium”. They claim that most fuel retailers are experiencing labor cost inflation, and must therefore raise their per-gallon price. But since MUSA locations do very high volumes, they can raise their prices less and continue to generate high fuel margins with best-in-class consumer pricing. I don’t buy this line of argument. In the model above, MUSA calculates that their competitors need to generate 1-11 cents per gallon more in gross profit to offset a minimum wage increase to $15 per hour, which would be a roughly 30% increase for gas station attendants according to Payscale. But passage of a $15 min wage is seen as a remote possibility. Also, it is not clear to me why stores couldn’t raise prices on convenience store items (where much of gross profit comes anyways), rather than gas prices. Finally, MUSA’s fuel margins have already increased >10c per gallon, so seem sure to fall regardless. I find it hard to believe that a bout of sub-10% inflation has somehow permanently changed the profitability of selling gasoline to consumers. We expect margins to fall back to historical levels. And if margins do fall back to historical levels, MUSA seems quite richly valued. The company trades at about 40x 2019 earnings. We’re going to pass on this one. If you haven’t heard, Twitter investors may be getting a slug of cash they need to put to work. This is a good thing, but it means we need to sharpen our pencils on where to reinvest this cash. The timing is decent, with the market down more than 20% and value indices also down double digits on the year. It’s time to turn over some rocks. I plan to read about at least one new company every day this month and will post the results here. First up is a company called PC Connection (ticker CNXN). Founded in 1982 to sell Macintosh computers, the company was named as the second fastest growing company in the US in 1987. In 1998 they IPO'd after growing 65% in the previous year. At year end 1999, the company had $1.1b of trailing sales, $22m of net profit, and a $550m market capitalization. After the tech bubble burst the company struggled with declining sales, and its market cap bottomed out at a mere $100m. This was the beginning of a very slow comeback in terms of both profits and valuation. Today the firm has a market cap of $1.2b on $3.3b of sales and $70m of trailing net income (about 17x PE). The share price has gone essentially nowhere since 2019. The business hasn’t changed that much, with PC sales still accounting for nearly half of revenue. The rest is made up of accessories, servers, and software. This is, unsurprisingly, a low margin operation, and EBIT margins have varied between 2.5% and 4% in recent years. But despite these low margins, high inventory turnovers and low fixed capital requirements give the firm around a 10% return on equity. Revenue growth has been rather anemic over the past decade, with sales increasing from $2.2b to $2.9b. This makes sense given the overall saturation of PCs in the modern economy as well as tough competition from both Amazon and OEMs selling direct to consumers. One thing that is notable about the stock is that almost no one talks about it. SumZero (a well-trafficked buy-side investment site) has zero writeups, and the most recent one on Value Investors Club (“VIC”) is from 2008, when it went by a different ticker (PCCC). That 2008 VIC writeup cites the stock’s valuation of “near tangible book value” as a key component of the thesis. In other words, it was not a pitch based on the quality or growth of the business. Such a thesis wouldn’t really apply in 2022, with the stock trading at around 2x book value. The stock also traded at about 3x EBITDA and 6x earnings in 2008, much cheaper than today. Sell side coverage is also non-existent, with only Sidoti and Raymond James covering the company. Clearly, this is the type of boring, ignored stock that could get mispriced.

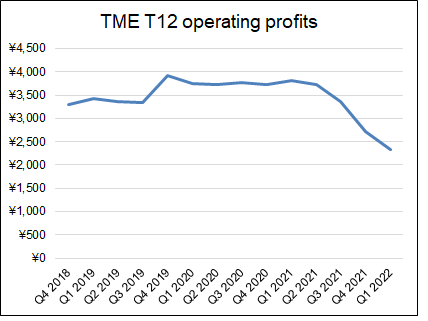

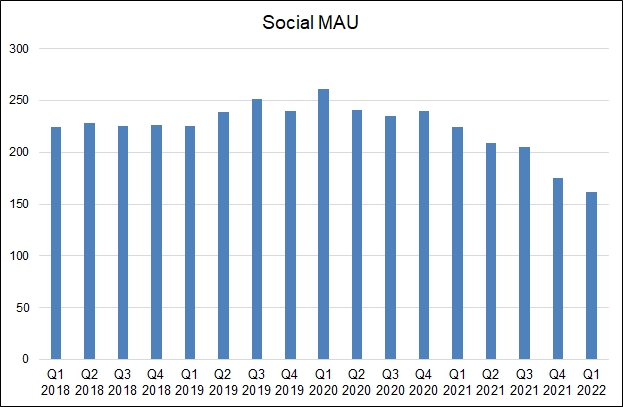

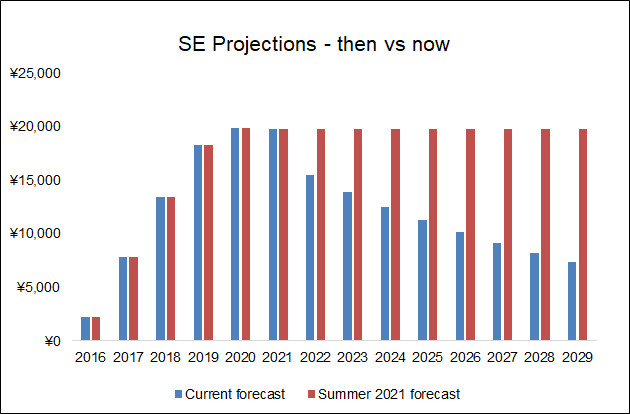

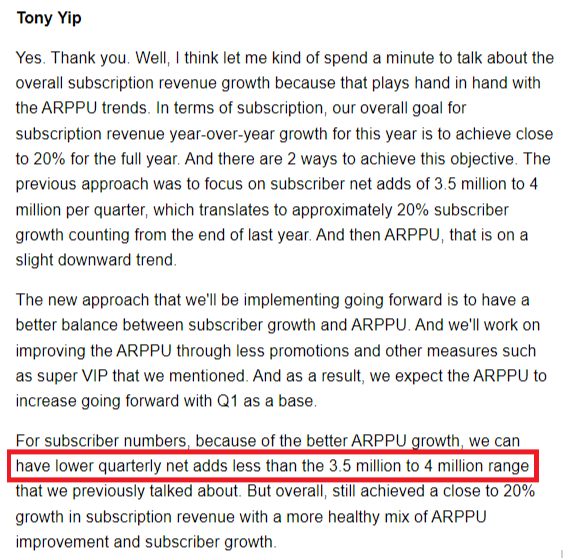

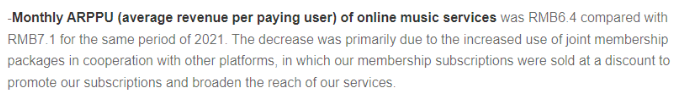

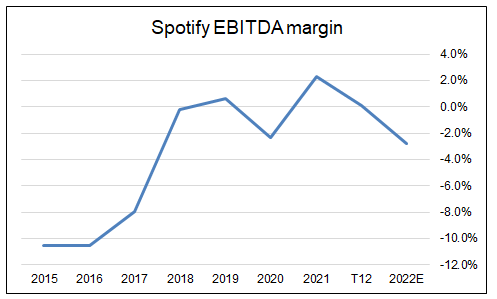

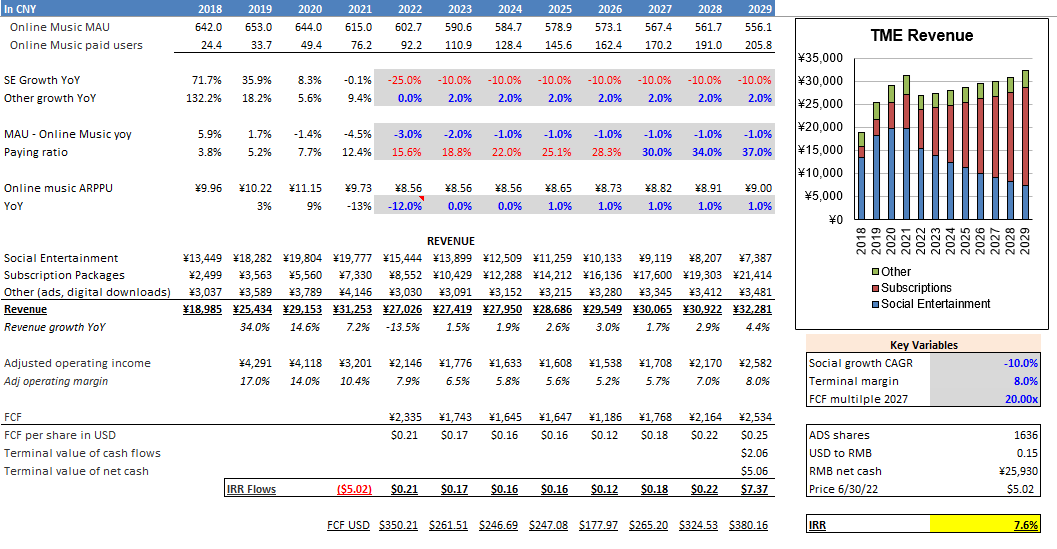

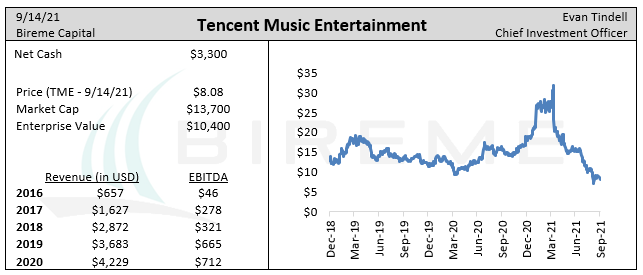

Still, given the business they are in, I fail to see why I should pay more than 10x earnings for this stock. If you want to invest in a business that sells PCs and accessories, why not own DELL or HPQ at 6-7x earnings? I’m going to pass on this one for now. Let me know if I’m missing something. We exited our position in TME in early Q3. Here's why. The original story When we invested in Tencent Music about a year ago, we said the following: With over 800m users across its many apps, Tencent Music is the primary way that people in China interact with online music. Today, the majority of revenue comes from virtual gifts sent to streamers in its “Social Entertainment” segment, which has grown revenue from $300m in 2016 to $2.9b in 2020. Within this segment, the most popular app is WeSing, a karaoke app with hundreds of millions of users in China. While competition from platforms such as Douyin (the Chinese version of TikTok) is increasing, WeSing continues to generate substantial profits for TME. The smaller segment (by revenue) is a subscription-based business similar to Spotify, utilizing a “freemium” model and providing Chinese users access to millions of songs. Their apps Kugou, Kuwo, and QQ Music have more than 600m users, but as of Q2 2019 more than 95% of them were on the free tier. Since then an aggressive effort has been made to grow subscription revenue, and 30% of songs are now behind a paywall. This shift has driven rapid growth in paid users, and today almost 11% of users pay for access to these songs. The size and consistency of this segment’s growth is extremely impressive. How many other companies can add 5m paid users per quarter? The theory was that the Social Entertainment segment, with EBIT of more than $500m, seemed to fully support the $8b enterprise value of the company. Separately, TME’s music subscription business was already doing around $1b of sales despite just having begun on their journey to monetize >600m unpaid users. This resulted in substantial upside should the growth of subscriptions materialize as we projected and the Social Entertainment business continued to throw off profits. However, our thesis failed on multiple fronts. As a result, TME has generated large shortfalls in operating income relative to our projections. While we thought the business would grow, profits are actually down around 40%. The problems at WeSing The decline in the Social Entertainment segment was the primary cause of the TME earnings drop, and this decline was driven by a fall in active users, which were down 27% over the past year. Prior to our investment, MAU’s had been moving lower, but we were able to convince ourselves that these were normal fluctuations around a base of 200-250m active users. But since we’ve invested, TME has posted another 3 straight quarters of user declines, making it 5 in a row on a QoQ basis. ARRPU (average revenue per paying user) growth could not overcome this, and revenues in the segment declined materially. We think this decline may be inexorable. While TME blames the drop primarily on “macro and industry” factors, not all streaming businesses in China are experiencing such declines. For example, Kuaishou grew DAUs by 17% YoY in Q1 2022. TikTok/Douyin almost certainly grew users in China, and Alibaba’s China Commerce (which includes live streaming platform Taobao Live) business grew users by 10% YoY. Netease Cloud Music – a key competitor which we will discuss later – grew paying users for their live streaming business by 61% YoY. So this is a TME / WeSing specific problem, and we don’t see why it would go away. It seems that users have simply begun to prefer other live streaming apps, and the platform's network effects may be working in reverse. YoY user declines have been accelerating, from the single digits a few quarters ago to 27% in Q1 2022. But even if the decline slows from 27% in Q1 2022 to 10% annually for 2023-2026, revenues would fall from 19b Yen to <10b yen. The graph below shows how our forecasts for this segment have changed. We think this implies just 1b Yen per year of operating profit from the SE segment in 2026. If the rest of the business is not profitable by that point (as it stands today), the company may only do 700 or 800m Yen of net profit, which is less than $200m USD. This figure does not compare favorably to TME’s $8b market cap. It doesn’t even look cheap against the current $4b current Enterprise Value, which subtracts the $4b of net cash and investments. Paying 20x five-year-out earnings is not a recipe for success. Online Music - will it ever be profitable? When we originally invested in TME, we expected the online music business to become profitable over time. But we did not invest in the company simply on this speculation; the valuation appeared well supported by profits in the SE segment. But with profits from that business collapsing, the long-term margins in the Online Music segment take on much greater importance. While the segment has been growing paid users, the other key input to revenue, ARPPU has disappointed materially. While we assumed 1% annual growth in ARPPU, it actually declined by 11% in the past year. While the company says that they expect ARPPU to increase going forward, with “Q1 2022 as a base”, they also implied that this may come at the expense of paid user growth: This is not a good sign. It implies that paid users are very sensitive to price, which is understandable but not what we had been expecting for a near monopoly. We had also assumed that the low absolute price of 9 RMB per month would allow for both user growth and ARPPU growth. One possibility is that we simply underestimated the strength of the competition, namely Netease Cloud Music (NCM). We assumed that a two-company market would act oligopolistically, and allow greater profits than the four-way slugfest between Spotify, Google, Amazon, and Apple in developed markets. But perhaps two aggressive competitors with a commodity product and a digital (ie, mostly fixed) cost structure is sufficient to create a race to the bottom in terms of pricing and profitability. NCM’s most recent quarterly results show that the company is in fact operating in a fairly aggressive manner. Paying users were up 50% YoY, to about 37m, and ARPPU fell from 7.1 RMB/mo to 6.4 RMB. In other words, NCM has dropped their effective pricing to a level that is 20% below TME’s. Here’s what NCM said about their decline in ARPPU: While both companies have an 8 RMB/mo bottom tier of pricing, NCM’s promotions may continue to exert downward pressure on TME’s pricing and/or user growth. Given this level of competition from NCM, it may be that TME’s long-term margins on the subscription business will not be materially different from Spotify's. This would be disastrous, since Spotify remains unprofitable on $12b of 2022e revenue. Even if Spotify eventually raises their margins, as their valuation implies they can, following in Spotify's footsteps would mean a very long road to profitability for TME's subscription business. By then, the Social Entertainment business may have withered to almost nothing. Projections Given what we know now, our current model for TME assumes the following:

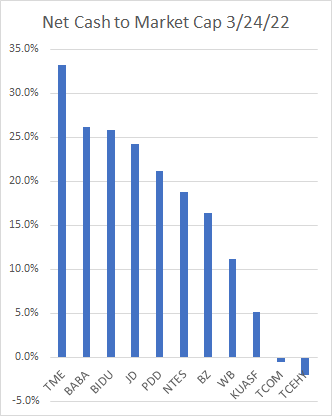

With these assumptions, the stock would generate a mere 7-8% IRR from current prices. Not terrible, but we have better opportunities. Due to geopolitical tensions, regulatory concerns and valuation compression, Chinese ADRs have taken a beating over the past year. The KWEB ETF, which tracks Chinese internet companies, is down nearly 70% from its peak. And even if we exclude the blowoff / Archegos top of Q1 2021, the index is still down 50% since late 2020. Some of these companies now trade at very attractive earnings multiples. As long-term value investors, this gets us excited. If management believes earnings are sustainable, they should use this dislocation to buy back shares at a discount. Buybacks would be very accretive to shareholders, and could catalyze a valuation rerating from the market. The question is: will management step up and pull the trigger? Or are they just as scared as the market? This is their moment of truth, and the firepower of these companies to do something is substantial: Some of these firms are taking action and have announced buyback plans. However they are generally quite small relative to the size of the net cash balances. Not a single one (that I’ve found) has announced a buyback that amounts to more than half of their net cash balance.

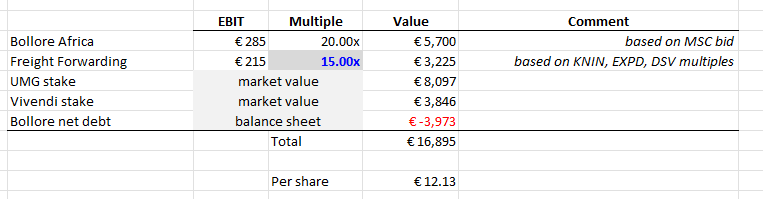

Tencent Music (one of our largest positions) said they’ve completed $553m of a $1b buyback that was authorized in 2021, and they will complete the rest in 2022. Still, this buyback is for less than a third of their net cash balance. Alibaba has increased their buyback plan from $15b to $25b. Still, this also amounts to less than a third of their net cash balance and less than a tenth of their market cap. Baidu announced that it repurchased $1.2b worth of shares in 2021, but has not updated the size of their buyback program (previously disclosed as $4.5b in total). To date their buyback pales in comparison to their gross cash of $27b and net cash of $14b. JD upsized its buyback program in December 2021 to $3 billion, but again this is tiny relative to $22.7b of net cash. PDD does not appear to have ever repurchased shares or commented on a buyback program, unless I’ve missed it. This is despite their net cash balance of $12b (21% of market cap). While we are heartened by the fact that companies like TME and BABA are making moves in the correct direction, all of these companies could go much bigger. Large buybacks could be a powerful signal that management believes earnings are sustainable, and a powerful catalyst for shareholders to realize the inherent value. Only time will tell if these companies will muster the courage to do so. Bollore is a French conglomerate controlled by Vincent Bollore. We have been shareholders for years and wanted to send out some updated thoughts. First, some background. Bollore's primary assets are Vivendi (29% stake worth around 4b EUR), Universal Music Group (18% stake worth around 8b EUR), and 100%-owned operations in African Logistics, Freight Forwarding and Electric Batteries. For more detailed thoughts on the individual segments, please see our full writeup from 2019. The market has never given Bollore full credit for these assets, even when those assets have been publicly traded. Today, Bollore's ~12b EUR worth of Vivendi and UMG almost gets you to more than the entire market capitalization of the firm when netted against ~4b EUR in Bollore-level debt. Essentially, the market is saying that Bollore's other businesses have no value. The "conglomerate discount" thus swallows up businesses which appear likely to do more than 900m EUR of EBITDA in 2021. There are a number of academic theories as to why the conglomerate discount exists. One driver is the principal-agent problem: management (the agent) simply has different incentives than shareholders (the principal). Management is incentivized to ensure and grow their own compensation, which may mean building an empire of diversified businesses rather than pursuing a higher-returning, more focused strategy. And just as important, management is incentivized to retain excess capital as opposed to paying it out as dividends. Inefficient conglomerates may be the result, and such firms trade a discount due to the implication that capital will be poorly reinvested. Academic research has found typical conglomerate discounts to be in the range of 10-15%. But of course the proper discount should vary based on the quality of management. Some conglomerates overcome the pull towards bad decision-making. Signs of this include: 1) Buying back stock when it is cheap 2) Paying large, chunky dividends 3) Selling off businesses when you get a good price 4) Spinning off key subsidiaries IAC Corporation (some background here) is a great example of this. Over the years, Chairman Barry Diller has maximized shareholder value at IAC, outperforming the S&P 500 and generating his multi-billion dollar net worth. IAC has executed more spinoffs than any other firm, and their progeny include such well-known businesses as Home Shopping Network (later QVC), TripAdvisor, Ticketmaster, Hotels.com, Expedia, Match, Vimeo and others. So when you own IAC, you know that the CEO (who answers to Diller) is not pursuing deals simply to increase the size of his empire -- he is going to spin them to you at the end of the day. Bollore is no stranger to spinoffs, with Bollore-controlled Vivendi recently issuing one of the largest in recent history. While the UMG spin was done downstream of Bollore itself, it indicates Vincent Bollore's willingness to shrink the fiefdom of his son Yannick, the Chairman of Vivendi. While Bollore still owns 18% of the company, UMG is now totally independent and no Bollore family members are involved in its operation. That business could be acquired at any time. But the most interesting move came more recently, when the family put its African Logistics business up for sale, hiring Morgan Stanley in October 2021. This resulted in a Christmastime offer of 5.7b EUR from MSC Group. This sale would be a massive change to the Bollore business, with the company's logistics arm exiting an entire continent. It requires the sale of a stable, profitable business which the family painstakingly grew over a period of decades. The price for this transaction seems to be quite good - about 20x EBIT. Not bad for something which is valued at zero by the stock market. It will be interesting to see what happens to this large chunk of capital should the deal come to fruition. Today, we think the total value of Bollore's assets is about almost 17b EUR today or 12 EUR per adjusted share. This implies a conglomerate discount of more than 50%, a level which is completely out of line with historical precedent. It also gives the Bollore family zero credit for the shrewdness of their recent moves nor their willingness to cede control of businesses when the time is right. We think Bollore stock will substantially outperform the market from current levels.

Elevator pitch

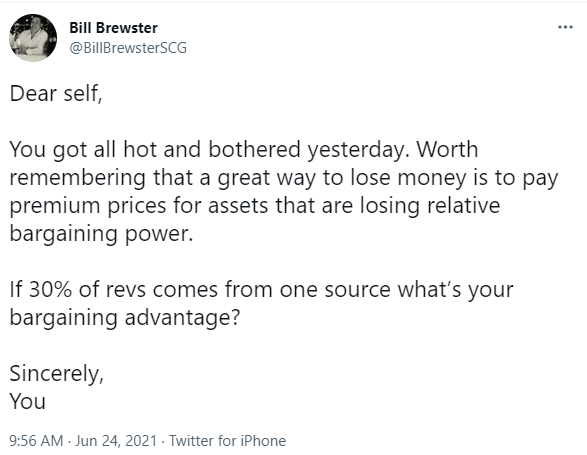

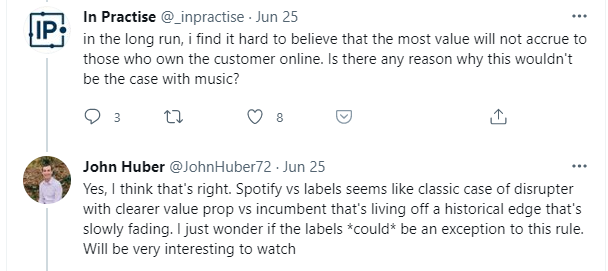

The history of Tencent Music is one of exponential growth, having increased revenues from 4.4b RMB to 32b RMB over the past 5 years. Today they dominate the online music business in China, with 800m users across multiple platforms. But despite generating nearly $5 billion in revenue, their subscription business has barely begun to scratch the service in terms of monetization. The stock price has collapsed in recent months, first with the liquidation of the Archegos fund -- a major shareholder -- and more recently with the decline of all stocks related to the Chinese internet sector. We think investors worried about the regulation of these companies are falling prey to narrative bias, attributing all actions by the Chinese government to a ruthless power grab. A deeper look reveals a government that is just reining in practices that would’ve been banned in Europe a long time ago. This is exactly the type of investor bias that we seek to exploit in our Fundamental Value strategy. The stock trades at a record low of just 14x ‘20 EBITDA and 17x ’21 EBITDA, a pedestrian valuation for a company that is likely to double its revenues over the next 6-7 years. We think investors buying today, at a stock price of less than $8, will generate an IRR of more than 15% over that time period. Famed podcast host Bill Brewster noted on twitter that he was worried about customer concentration at a company he was researching. The company had 30% of its revenues coming from a single firm. In many cases, a 30% customer has tremendous power over its suppliers. Let's consider some examples. Walmart v Blendco For most consumer product companies, Walmart is a major customer, often 10-20% of sales. Walmart uses this fact to its advantage, resulting in headlines like this: This is part of Walmart's moat: their scale results in a positive feedback loop between low prices, customer traffic, and supplier negotiating power. Low prices —> High customer traffic —> Power over supplier —> Supplier cuts prices —> Lower prices To show how this works in practice, let’s war game a conversation between Walmart and a supplier of say, blenders: Walmart: We need you to lower your prices Blendco: We don’t want to Walmart: If you don’t, we will bring in another supplier of blenders Blendco: But our products are unique. People will be up in arms if you don’t carry our blenders! You will lose traffic! Our loyal customers will go online to buy our blender anyhow! Walmart: I don't think so Blendco: Eeek Walmart's success in this negotiation hinges on customers not caring much about differences in blender design. They may have a slight preference, but most wouldn’t notice if Blendco’s products disappeared from Walmart's shelves forever. In contrast, Blendco cannot recover this revenue. So most of the time, Blendco caves and offers Walmart a slightly lower price. But not all large customers have this type of power. Spotify v UMG For music labels, Spotify is an even larger customer than Walmart is in the consumer products world. For example, payments from Spotify constitute roughly 20-30% of Universal Music Group (UMG) revenue. This was the inspiration for Bill Brewster's tweet. The idea is that Spotify may be able to leverage this position and its "ownership of the customer relationship" to retain more value for themselves over time. The "customer ownership" theory appears to rely on experience from other online media businesses, where such ownership was key to long-term success. The obvious example is Netflix, where the relationship with its ever-expanding set of consumers has created the industry's largest budget for exclusive content, improving the product dramatically relative to competitors and driving even more subscriber signups. The problem with this analogy is that Netflix has always had a differentiated product relative to peers. Much of their content is unavailable to be streamed elsewhere, and they've always had far and away the most scale. Spotify has none of these advantages. In music, it has ~zero exclusive content, and while it does have the largest subscriber base, their scale advantage is modest relative to Netflix's. We think a hypothetical negotiation between Spotify and UMG would look like this: Spotify: We need you to lower your take rate UMG: We don’t want to Spotify: If you don’t we will bring in another supplier of Drake and Taylor... ok we can’t do that. Well, we will just drop your songs from Spotify completely. Our consumers won’t care. Maybe we can lower our prices. UMG: You don’t think your customers will jump to Apple Music or YouTube Music if you don’t have Taylor Swift, Billie Ellish, Drake, The Weeknd, The Beatles, Post Malone, Lady Gaga, and Ariana Grande? Spotify: Eeek In this negotiation, the fact that Spotify provides 30% of UMG’s revenues is almost irrelevant. While Spotify appears to own the customer relationship, at the end of the day it is a music app. The music is really what owns the relationship with consumers. Yes, there may be some consumers who feel locked in to Spotify due to playlists they’ve shared or followed. But for most people, the loss of UMG artists would would far outweigh other considerations. They would simply switch apps. Daniel Ek is too smart to take that kind of risk. Musicians v UMG What then, about the stars? Can't they use their leverage to get a bigger slice of the pie? The short answer is that they will try to, and they do have some leverage. After all, these stars control important music: their yet-to-be-recorded albums, at least those that are not under existing contracts. The back catalog will be owned by UMG regardless, but many stars have woken up to the long-term value provided by streaming and want to have greater ownership over their future music. They will be tough negotiators when current contracts run out. But wasn't this dynamic true before streaming? It has always taken a lot of money to retain hit musicians with expiring contracts. Somehow this fact has not crushed the economics of labels historically and I don’t see why streaming changes the picture, other than giving both sides a larger pie to split. Stars going independent What about the artists building an audience on social media and then going completely independent? This could happen, to be sure. But the evidence shows that artists continue to value working with the major labels. And why wouldn't they? The music industry is notorious for creating one-hit wonders. The real skill is in turning one hit into two, three, and four hits. That is what makes a career in the music industry and labels still bring considerable expertise to bear on this effort. Consider Lil Nas X. He uploaded the original Old Town Road track in December 2018. Note the request in this tweet: The song went viral on TikTok and elsewhere a few months later. He had all the attributes of an act that could've gone independent: 1) He produced his own music 2) He uploaded his songs to streaming services using an independent distribution provider 3) He gained traction on social media before signing anything All of this gave Lil Nas X leverage. Theoretically, he could have just uploaded his music to Spotify using something like CD Baby and raked in the $$$ without splitting it with a traditional label. But he didn't. He decided to sign with Columbia Records. In fact, he appears to have turned down a $1m+ offer from his original distribution platform / independent label Amuse. So far, this decision appears to be working well for him. After all, it was Columbia Records head Ron Perry that contacted Billy Ray Cyrus about appearing on a version of the song. That "remix" is now the official version, the one that broke the record for longest run at #1 on the Billboard charts. I don't think Lil Nas X is regretting his decision. While we have no doubt that some artists will go the independent route, and that social media will help them do so, we think the majority of breakout artists will want help. And that help is likely to come from the labels with the best track record of creating stars, with UMG at the top of the list. All of this being said, we continue to think that the best way to get exposure to UMG is through the extremely-discounted stock of Bollore. |

What this isInformal thoughts on stocks and markets from our CIO, Evan Tindell. Archives

December 2023

Categories |