|

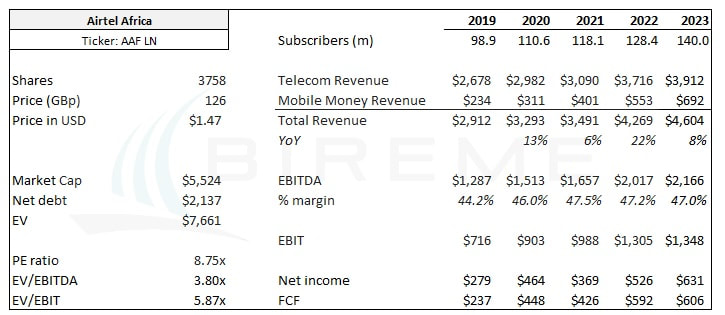

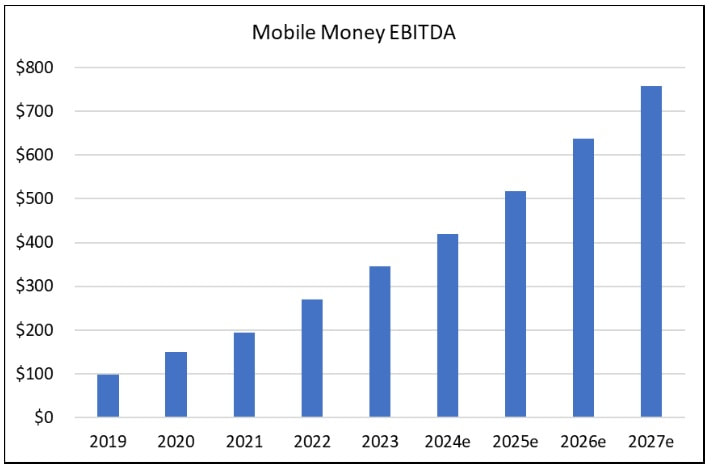

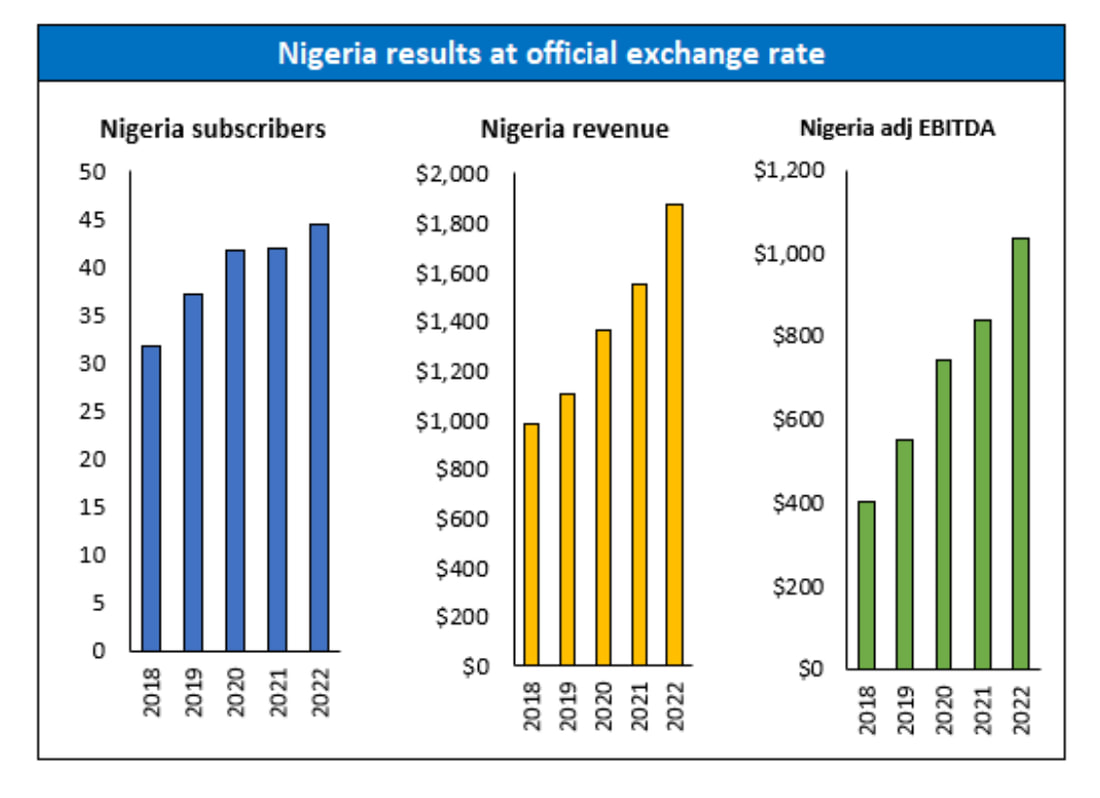

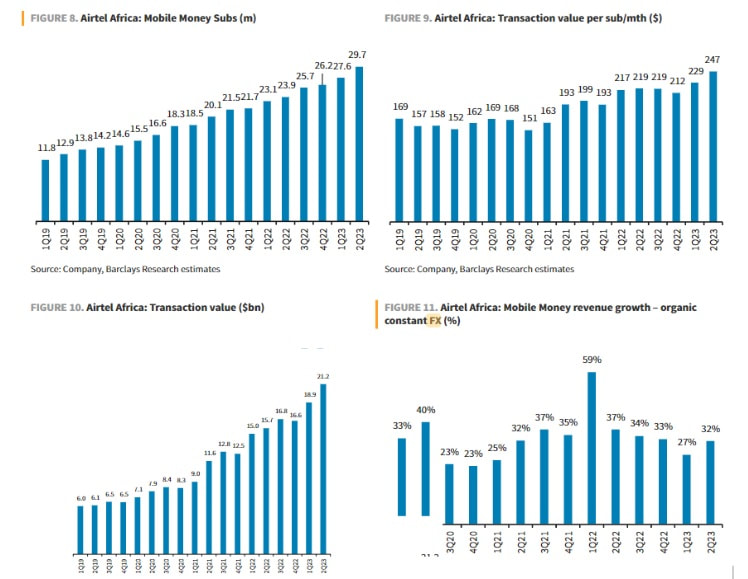

Introduction Airtel Africa is a profitable, high growth, yet very cheap telecom business operating in Sub-Saharan Africa. At a market cap of about $5.5b USD, the price-to-earnings ratio is less than 9x. On an EV basis, the company trades at just 6x EBIT. This valuation gives the company no credit for the tremendous historical growth and potential growth runway. Since 2017, revenue has grown by two thirds, from $2.8b to $4.6b, and EBITDA has more than doubled $2.1b. Biases at work We think the company’s valuation suffers from what we call “lazy grouping bias” — investors seem to value it like a traditional telecom company with low growth, stiff competition, and high capex needs. But it’s growth profile and returns on capital (even after depreciation) show that it is nothing like a mature Western telecom firm. The stock’s valuation may also be suffering from familiarity bias, the tendency for investors to focus on stories they know and understand well. Airtel’s operations are across 14 African countries, but it trades in London, reports in US dollars, and is majority owned by an Indian telecom operator. The stock has no natural investor base, and perhaps explains why the stock consistently trades at a discount to lower-growth peers Safaricom and MTN, which are locally listed in Kenya and South Africa respectively. Or perhaps investors worry that the company cannot recoup currency devaluation via local pricing growth. While Airtel does operate in emerging Africa, it is different from many companies in the region in that it has shown an ability to grow consistently in US dollar terms, even after accounting for black market exchange rates. We think it is likely to continue to do so. In fact, given the low rate of penetration of both phone and data service in its markets, AAF should grow quickly for the next decade. We also think it should continue producing >40% EBITDA margins and >30% EBIT margins, roughly double the EBIT margins of US-leading TMobile. On top of that, availability bias may be causing investors to ignore the firm’s hidden gem: the mobile money segment. This peer-to-peer transfer business will facilitate more than $100 billion in transfers this year. This translates to $600-700m of revenue and $300m+ of EBITDA for Airtel Africa. Users, dollar value transferred, revenue, and EBITDA have grown almost every quarter since Q1 2019 (see chart in appendix). We think investors willing to take the currency and geopolitical risk inherent in Airtel will be handsomely rewarded. Company history Airtel Africa is controlled by Bharti Airtel, one of the largest telecom companies in the world. Bharti Airtel was founded in the early 1990s by Sunil Mittal. Originally, his businesses assembled phones and fax machines. In 1992 he bid for a telecom license, and partnered with Vivendi to start the firm in Delhi. In 1995, Bharti Cellular Limited was formed and began to offer mobile service under the name “AirTel”. By 2005, and after multiple acquisitions, it was providing cell phone service across all of India. The firm is known for its ruthless outsourcing of non-core activities, including technology. Contrary to nearly all advice being offered at the time (ibid), Airtel hired Ericsson and other European firms to build its core network. This lowered its costs, allowing Airtel to price the service at or below the competition while still generating substantial margins. The firm achieved an EBITDA margin of 52% last year and total customers have grown to an impressive 500m. The company branched out to Africa in 2010, buying the operations of Zain Telecom, a Kuwaiti firm with operations across the Middle East (and Africa up until 2010). Zain itself had built its African business via acquisition, purchasing the 24m-subscriber Sudanese firm “Celltel” for $3b in 2005. By the time Airtel took over, the business had 40m subscribers and sports over 130m today. Bharti Airtel continues to own 55% of the shares, and they seem properly focused on shareholder value. The company has paid a growing dividend over time, including $200m — or one third of overall profit — last year. Airtel’s telecom business Relative to western countries, Africa is still under-penetrated on mobile service. Only 54% have cell phones. In the US and Western Europe, the number is closer to 100%, with many adults having two phones. There is also significant population growth in Africa, including 2% growth in 2022 vs none in Europe. This combination of demographics and under-penetration has allowed Airtel to add subscribers consistently over the years, from 24m in the Celtel days to 135m today. We think this is likely to continue. Usage has also grown tremendously, from a very small number of phone minutes to 270 minutes per line per month today. Data has been exploding in Airtel’s footprint. Data traffic grew 45% in H1 of FY 2023, despite only 45% of Airtel’s customers being on 4G. We think data usage will continue to grow rapidly given the average user only downloads 4.5 GB per month, less than half that of Europe. Eventually, data traffic per user may even be higher in Africa than in western countries because the smartphone is typically the sole household data source. In the US, households are pulling 600GB per month in data on their fiber connections. Data revenue is key to the story of how Airtel can combat inflation. In general, the company has to ask permission from the government before raising prices. Governments are reluctant to approve these price increases, which are not very popular with voters. Normally, sticky prices make it very difficult to deal with inflation. But telecom service is priced per GB, and costs per GB tend to fall over time as data use grows. In most countries, competitive pressures then drive lower and lower prices per GB. In the US, the effective price per GB has declined at a 10% CAGR. If the price per GB is flat, this implies significant price inflation relative to the natural state of the industry. This solves Airtel’s problem, as the company can effectively combat inflation by simply keeping prices flat rather than declining. It also explains how Airtel’s USD-translated ARPU has stayed roughly flat despite material currency devaluations over the past 5 years. Steady ARPU plus a rise in subscribers has meant revenues increasing from $2.7b to $4.5b since 2017. The business also has material operating leverage, with EBITDA in the telecom business growing from $700m to $2b in that time. Mobile money business In sub-Saharan Africa, roughly 50% of the population still does not have a bank account. This means that, historically, the only way for them to transact in the economy was to carry cash or perform some kind of barter. Cash is risky - it can easily be lost, stolen, or ruined. And of course bartering with goods or services is extremely inefficient. Individuals in Kenya started to solve this problem in the early 2000s by swapping cell phone airtime as a proxy for money. Researchers noticed this, and a solution was proposed whereby SIM holders could officially transfer money to each other. The pilot for M-PESA was rolled out by Safaricom (owned 40% by Vodafone) in 2005, and quickly became the dominant form of money transfer in Kenya. The growth of M-PESA has been nothing short of stupendous, and users transferred 18 Trillion Kenyan shillings in the first half of Safaricom’s fiscal 2023. This is the equivalent of $137b US dollars, or more than an entire year’s Kenyan GDP! Essentially 100% of the formal Kenyan economy apparently flows through M-PESA, and then some. According to researchers at MIT, M-PESA has lifted hundreds of thousands of Kenyan households out of poverty by reducing friction in the economy and moving transactions away from cash. Airtel started Airtel Money to provide a similar service to its SIM-holding customers. The uptake has also been dramatic, with over 30m subscribers using the service and $25b being transferred last quarter.Airtel’s take rates on these transactions are relatively low, below 1%, but margins are high. Airtel generated almost $350m of EBITDA from this line of business in fiscal year 2023. The upside seems large for this segment, given that only 30% of subscribers (excluding Nigeria) use the service and this seems likely to approach 70% or 80% over time. In our base case, I forecast Mobile Money to generate $1.5b of revenue and $750m of EBITDA by 2027. The value of this business is not lost on management, who raised money from US private equity firms and Mastercard for the segment at a $2.65b valuation in early 2021. The segment is arguably worth materially more today, something which is clearly not appreciated by public market investors given Airtel’s $5b market cap. This is probably why the company has plans to list the business within the next four years: “Let me start with the last one on the listing of the mobile money business. Last year in March 2021 when we announced that we’re selling down some minority stake, we mentioned that within four years we’re going to do an IPO. That guidance has not changed. We’re still looking at a four year period within which we’re going to do an IPO.” Given the growth trajectory of this business, we think it would trade at more than $5b if it were a separate company. This would equate to 14x trailing EBITDA and about 6.6x my 2027 EBITDA projection. Nigeria Nigeria, a nation of more than 200m people, is one of Airtel’s biggest markets and one of its three major geographical segments. It is unique enough, and large enough, that it is worth talking about separately. Airtel Nigeria’s customer base is 47m, making the company #2 in market share behind MTN, which has over 80m. Airtel’s sub count has grown consistently over the years, and was up 9% YoY in the most recent quarter. Notably, only 23.8m customers – just half of subscribers – have data services activated. It seems highly likely that this will trend towards 100% over the next 10 years. Data usage per customer has grown as well, up 25% on a YoY basis last quarter. In other words, like in its telecom business overall, Airtel has multiple levers to grow in Nigeria:

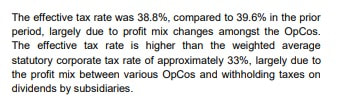

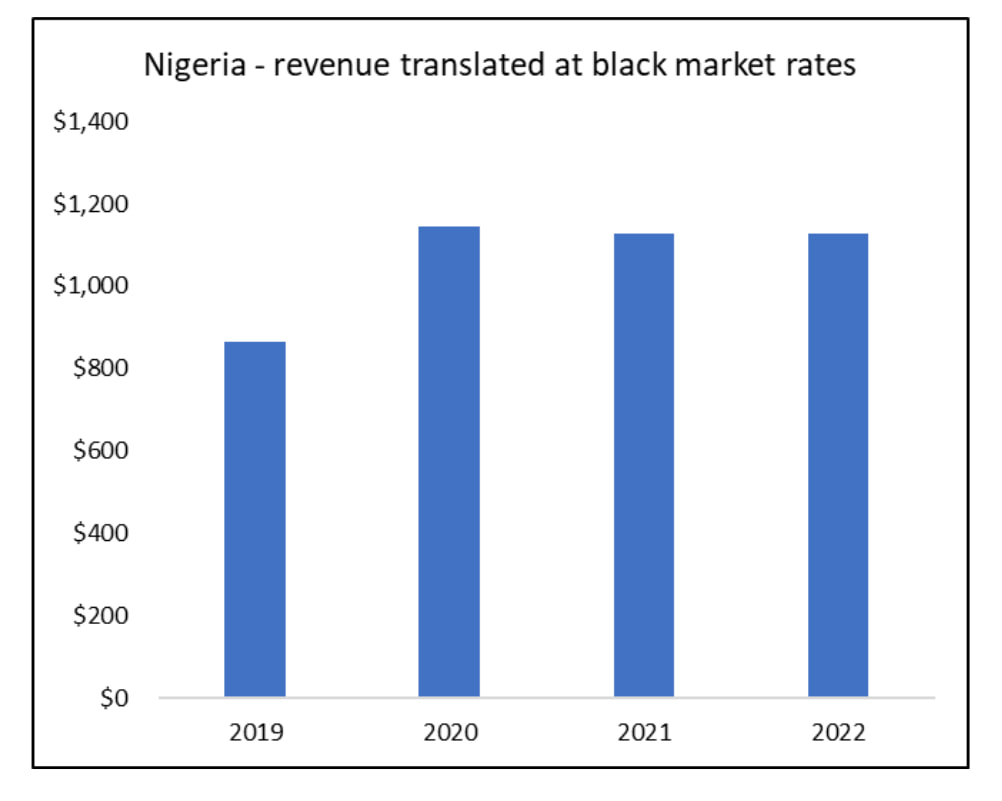

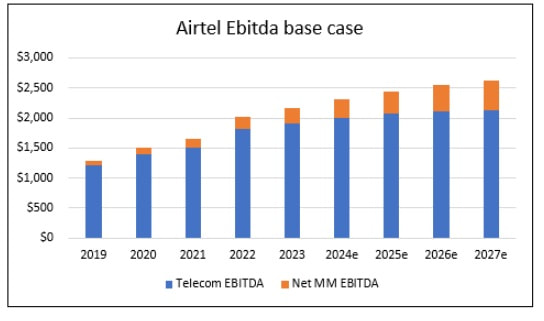

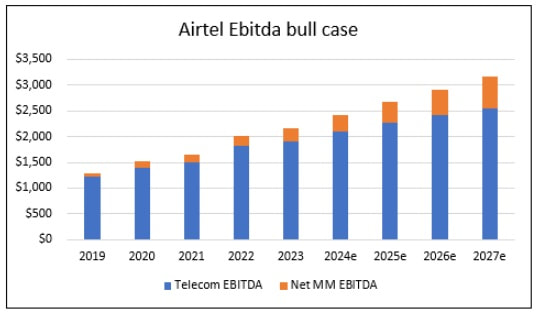

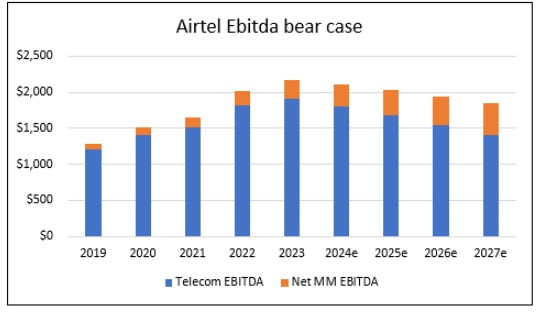

These levers have combined to generate tremendous revenue growth in the country, despite a 2020-21 freeze in mobile signups instituted by government regulators. Given that capex has been running $200-300m per year in the country, EBITDA - capex appears to be $700-800m. In other words, the business generates substantial free cash flow in Nigeria. Regulation in Nigeria This profitability is well known to regulators, who try to get their piece of the pie. Nigeria’s corporate tax rate was 30% in 2022, a bit higher than the world average of 23.5%. This is consistent with other African nations, which are typically >25%. Airtel Africa’s weighted statutory is about 33%, although they end up paying about 40% when accounting for withholding tax on dividends. From the Q3 FY 2023 investor pack: Spectrum regulation is another way governments profit from the telecom industry. This is not unique to Africa, with the US government bringing in $81b from a 2021 spectrum auction. Nigeria held spectrum auctions beginning in 2021, when MTN — the largest operator — won the bidding to license 5G spectrum. But in late 2022, after regulators pressured MTN not to participate, Airtel emerged as the sole qualified bidder for an additional 100 MHZ of 5G spectrum in the 3500MHz band. The auction was canceled and Airtel paid $317m for the right to use these airwaves. This price seems reasonable to us given the hundreds of millions of EBITDA that seems likely to flow from the rollout of 5G service to its customer base. Currency in Nigeria Currency fluctuations are a key pain point for international corporations in Africa. Nigeria is no exception, and the Naira has depreciated from 22 per dollar in 1994 to over 400per dollar in 2023. This is a rate of roughly 11% per year. And still, Airtel’s business has grown substantially in dollar terms. The company has increased prices over time as local currency depreciates, and both MTN and Airtel raised prices per GB in 2022. Unfortunately, the official government exchange rate does not tell the whole story. Due to high demand for US dollars and other “hard” currency, the Nigerian government limits the amount of Naira that can be exchanged at the central bank. If you want unlimited conversion, you must go to the black market, where exchange rates offer US dollars only at a premium: currently more than 700 Naira per dollar. If we convert the currency at black market rates, growth in the country nearly disappears. This is because the gap between the two rates has risen substantially in recent years. And yet, for the most part, the company is able to repatriate dollars at the “official” rate. In Q3 2022 they said they had repatriated $300m out of Nigeria in the trailing 9 months, which was a majority of FCF during that time period. To be extremely conservative, we value the Nigeria business at black market rates and assume little growth going forward. This puts the stock at about 10x earnings and 9x free cash flow at today's prices of around 120 Gbp per share, still cheap by just about any standard. The Naira appears to be the main problem currency in Airtel markets. Many of the other currencies are free-ish floating and have tended to depreciate vs the dollar at around 10% per year historically. But this depreciation is captured by Airtel’s USD-based historical financial statements, and they’ve grown USD revenues anyhow. By and large, we expect Airtel to be able to keep flat to growing USD ARPU via usage growth and occasional price increases. There is further currency analysis of Airtel’s other markets in the appendix. Mobile Money in Nigeria For years, Nigeria has been one of the only countries in Africa to not allow mobile money. There have been debates about regulation, with the Nigerian Central Bank for example demanding in 2020 that “payment service banks” retain at least $13m of capital and refrain from making loans. Apparently, much of the regulatory framework was held up by bank lobbying, and did not begin to become fully clear until the Central Bank issued a regulatory framework document in July 2021. This regulatory framework states that the “Telco Model” shall “not be operational in Nigeria”. Instead, mobile money can only be operated by a “Lead Initiator” that is specifically licensed for the purpose. This doesn’t have to be a bank, but it does have to be an entity that is answerable to the Central Bank. Given all the restrictions in place, and how late in the game Nigeria has allowed mobile money, we are not convinced that this will be a highly profitable MM market for Airtel. There is more competition from the start and the market may not fully develop the way it has in the rest of Africa. Still, the opportunity is vast. If Airtel was to achieve a 20% MM penetration in its telecom subscriber base — far lower than the 40+% the company is moving toward in other geographies — it would probably generate $100-150m in revenue for the company. At 50% EBITDA margins and little need for capex, this could materially add to the free cash flow of the enterprise. It remains to be seen whether this can be achieved, but either way it does not appear that we are paying for this potential at the current valuation. IRR and conclusion We forecast Airtel’s results in three scenarios: a base case, a bull case, and a bear case. In each of them, we forecast telecom subscriber growth from 140m to 170m over the next 4 years. The company added 41m subs in the previous 4 years, so this is in line with historical growth. Mobile services are still <50% penetrated in the company’s footprint. In all cases we use the black market exchange rate for the Nigeria segment. We then vary the following key factors:

Base case

In this scenario, FCF grows from $592m in 2022 to $843m in 2027. The IRR is 23% from the current price of around 120 GBP per share. Bull case

FCF grows from $592m to over $1b in this case. The IRR would be 37%, and we would more than triple our money in four years. Bear case

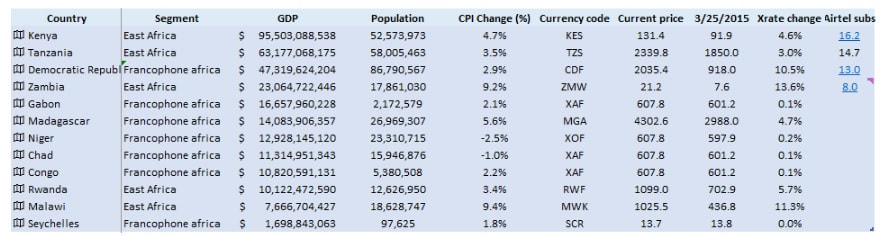

FCF in this scenario drops from $592m to $514m, and the IRR of our investment is -1%. This bear case does not include true outlier possibilities like a country’s telecom industry being expropriated. However, we think it is sufficiently conservative to represent a reasonable downside scenario. Given the valuation and current trajectory of the business, it just appears difficult to lose much money. We made a significant investment in Airtel Africa in early Q2. Appendix Mobile Money slide from Barclay's mentioned above: More on Airtel’s currency risk Airtel’s markets outside of Nigeria, ranked by GDP: Below I discuss some of Airtel’s major currencies, in order of importance. The main point of this discussion is to try to determine the prevalence of black-market currency rates in Airtel’s markets. Parallel currency markets can be taken as indication that the official rate is overvalued, and Airtel’s USD financials may not be accurate in a PPP sense and may overstate the economic value of the business. Kenyan shilling The Kenyan Shilling has depreciated about 5% annually since 2015. This is unremarkable as far as emerging market currencies go, but the slide has accelerated in recent years. The Kenyan exchange rate is not a truly market-based price, and importers are talking about a “dollar shortage”. Quartz reported in March that the Central Bank was “running out of dollars”, and a black market rate has emerged. Unlike Nigeria, though, black market prices seem to be within 10% of official rates, indicating that Airtel’s USD financial information from Kenya is probably roughly correct. Airtel has 16m subscribers in Kenya, and is Airtel’s largest market outside of Nigeria. It has grown market share over the years, from about 20% in 2017 to 26% today. This market is dominated by Safaricom in both phone service and the mobile money business. Tanzanian Shilling The Tanzanian Shilling has depreciated about 3% per year since 2015, a very reasonable rate. However, this comes after a large move in 2014. Since 2003, the rate of change has been more like 10% annually. However, I have not found evidence of a parallel currency market in the currency. In fact, during Kenya’s dollar shortage, businesses have apparently been turning to Tanzania to get dollars. This indicates to me that the Tanzanian government must be exchanging these on a somewhat free basis. Airtel has around 15m subscribers in Tanzania. Congolese Franc The currency of the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Congolese Franc has depreciated 22% annually since 2003 and 10% annually since 2015. The government sometimes intervenes in the exchange markets, and from the chart below it is clear that the currency is under a “managed float” regime. Airtel has 13m subscribers in the DRC. Zambia Kwacha Zambia’s currency has been the worst performing since 2015, depreciating by 14% per year. There does seem to be a parallel market, but I couldn’t find evidence of prices in this market. XAF / XOF Currencies The Central African Franc and the West African Franc are pegged to the Euro and backed by the French Treasury. This peg has been consistent since the late 1990s, when they were devalued to allow these country’s exports to become more competitive. There has been no devaluation since. Conclusion on currency Aside from Nigeria, there does not seem to be major parallel markets for Airtel’s currencies that would indicate that they are materially overvalued. Even in Kenya, where the black market is a problem, prices are within 15% of the official rate. In my view, the cheapness of Airtel stock more than makes up for the potential for currency devaluations. We expect Airtel to be able to maintain roughly stable USD pricing in most localities, and continue to benefit from population growth, market share increases, data usage expansion, and the vast potential of the mobile money segment. Even still, our base case assumes a decline in telecom ARPU, implying that local currency ARPU growth is more than offset by depreciation. And yet it still delivers a >20% IRR. Bireme Capital LLC is a Registered Investment Advisor. Registration does not constitute an endorsement of the firm nor does it indicate that the advisor has attained a particular level of skill or ability. This piece is for informational purposes only. If not specified, quarter end values are used to calculate returns. While Bireme believes the sources of its information to be reliable, it makes no assurances to that effect. Bireme is also under no obligation to update this post should circumstances change. Nothing in this post should be construed as investment advice, and it is not an offer to sell or buy any security. Bireme clients may (and usually do) have positions in the securities mentioned. Advisory fees and other important disclosures are described in Part 2 of Bireme’s Form ADV. Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk and there can be no assurance that any specific investment will either be suitable or profitable for a client’s investment portfolio. For current performance information, please contact us at (813) 603-2615.

Comments are closed.

|

What this isInformal thoughts on stocks and markets from our CIO, Evan Tindell. Archives

December 2023

Categories |