|

Clayton Christensen is an HBS professor that coined the term "disruptive innovation". The theory His theory states that disruption is made possible by low-end (read: cheap) or new-market footholds. Incumbents have little incentive to match prices with low-end disruptors since it would hurt their margins. This allows the disruptor to gain market share with little direct competition. Eventually, their product improves and becomes "good enough" for a large segment of the market. At this point it may be too late for incumbents to change course. Often the disruptor has developed new manufacturing or distribution methods (with the original goal of lowering costs) that make their strategy harder to imitate for the market leaders. In my view, Christensen's theory focuses too much on price. In fact, he seems to think that no innovation should be considered "disruptive" if it doesn't begin at the cheaper end of the market. To the extent that he is defining his own term, I guess this is okay. If you invent a phrase you can define it however you like. But Christensen's narrow definition of "disruption" makes the theory useless for investors. It has also led the professor to make some foolish statements about particular companies:

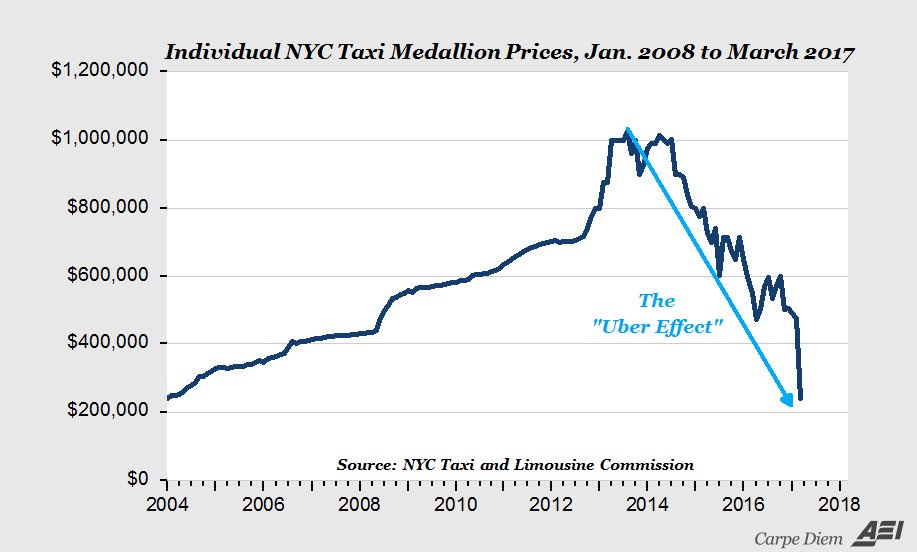

In these cases we see Christensen taking a narrow definition of "disruption" and using it to make a forecast. In all three cases he was wrong, in the sense that Apple, Uber, and Tesla investors have been richly rewarded (especially compared to incumbent phone manufacturers and taxi companies). Besides potentially misleading investors, this narrow definitive of "disruption" doesn't match the normal use of the word. Isn't Uber disrupting the taxi industry in under any sane definition? Look no further than NYC taxi medallion prices, which have completely collapsed since 2013. There have even been taxi driver suicides in some extreme and saddening cases. The fact that this disruption began with high-end black cars didn't enhance the taxi industry's ability to stop it. Uber is not the only company to disrupt industries despite failing to conform to Christensen's definition. To be sure, competitors starting at the low end of a market attract less attention from incumbents. But even in the examples described in Christensen's writings, non-price factors play a key role in the gains made by disruptors. Minimills A portion of Christensen's early work on disruption focused on North America's integrated steel mills. In the Innovator's Dilemma, Christensen describes the plight of these firms. He tells how Bethlehem Steel and U.S. Steel have fallen prey to stiff competition from "minimills". Minimills are smaller plants that make steel by melting down scrap metal in electric arc furnaces. Integrated mills, by contrast, are much larger and make steel from scratch. Essentially, Christensen calls the managers of integrated mills stupid for not investing in the minimill technology which would eventually disrupt their business: "The closing of these major steel complexes is the final dramatic concession from today's chief executives that management has not been doing its job." - Innovator's Dilemma, pg. 80 But what if U.S. steel was correct to ignore the minimills? After all, while the two businesses seem superficially similar (both make steel, after all) running a minimill is vastly different than running an integrated mill on a number of fronts:

All of these are consequential to the structure of the business. It is not true that "scale is the only difference" as Christensen claims in Chapter 4 of the Innovator's Dilemma. For example, the difference in possible locations propagates massive changes down through the business. Let's look at a 1983 NYT article about Nucor (a successful minimill operator) to see what this implied. Its four steel plants all are located in low-wage rural areas of South Carolina, Nebraska, Texas and Utah, where anti-union sentiment is strong and hard work is an article of faith. Because minimills take scrap metal and not raw material as inputs, they don't need to be on waterways to receive shipments of ore and coal. This flexibility of location allowed Nucor to use non-union labor, vastly improving their cost structure. This is not something that integrated mills could've copied without angering (and potentially violating agreements with) their unionized workforce. But despite the myriad operational differences between the two types of steel plants, Christensen focuses on price, claiming that the lower margins on minimill products were the main reason this technology was ignored by incumbents. He does this, it seems, to match the results with his theory that a low-end foothold is key to disruption. This is exactly the type of myopic focus on price that caused him to misunderstand the disruptive capacity of the iPhone. More counterexamples In some cases the business model of the new competitor is so different that incumbents cannot respond regardless of whether the new product has cheaper prices. I'll return to Uber is probably the most obvious example. The skill set required to run Uber's business could not be more different than the old taxi model. Taxi operators simply need a license and the ability to drive. In contrast, Uber has to:

The list goes on and on. In my view, it is abundantly obvious that taxi companies were never going to be able to compete. Of course, this is not the only example. Below is a list of obviously-disruptive companies whose key differentiating feature was something other than price. Apple - Phones. Christensen saw the iPhone as a 'sustaining innovation': "The iphone is a sustaining technology relative to Nokia. In other words, Apple is leaping ahead on the sustaining curve. But the prediction of the theory would be that Apple won't succeed with the iPhone. They've launched an innovation that the existing players in the industry are heavily motivated to beat. In the end, he was wrong: Nokia was "highly motivated" to respond but ultimately could not. As a company focused on hardware, they simply did not have the programming or design talent to succeed in a software-based world. Blackberry had the same problem. It ultimately took a software-focused company (Google) to compete with Apple in the smartphone market. But even that competition didn't doom Apple -- despite the low (dare I say "disruptive") prices of many Android models -- because customer preference for good software, and especially software they are familiar with, is one of the world's strongest competitive moats. Low prices alone cannot overcome it. Facebook and Google - Advertising. Google and Facebook have certainly disrupted the advertising industry, making programmatic ad buying common and taking a huge portion of industry revenues. Their ad products are not particularly cheap, and their customers aren't new to advertising. But their advertisements are better targeted and give the buyer more data than legacy ads. Obviously, it is difficult for TV or print to respond given the limitations of those platforms. Intuitive Surgical - Minimally invasive surgery. Intuitive's surgical robot is much, much more expensive ($1m+ per machine, plus more for consumable parts) than previous methods. But it is better for patients because it allows minimally invasive surgery to be performed more often and more effectively. Incumbents can't copy them because Intuitive has a huge technological lead and it would take years for competing products to secure FDA approval and hospital acceptance. In addition, the large installed base of robots means that most surgeons train on them during residency. The robot's high price does nothing to help incumbent providers like Medtronic compete. Align Technology - Translucent tooth alignment. Align's products are roughly 2x the cost of normal braces, but look a lot better while in use and are clearly disrupting that industry. Under Christensen's framework, existing braces providers would've simply copied Align, but this hasn't happened, probably due to differences in the technology. The stock is up 13x over the last ten years. SiriusXM - Satellite distribution of radio content. Sirius is way more expensive than radio: $10-20 per month rather than free. However, because satellites provide a nation-wide signal, as opposed to the geographically limited range of radio, Sirius can have a much larger subscriber base. This supports investments in exclusive content which enhance the quality of the product and create a virtuous cycle. Christensen might've had you believe that radio stations would seize this "sustaining" innovation and launch their own satellites. Of course, this has not happened. Conclusion These examples do not imply that price is irrelevant. Innovations that result in lower prices have spawned many successful businesses, including Netflix, T-Mobile, Walmart, Amazon, and Steam to name a few. All of these used industry-leading discounts along with new business practices to make huge profits for their owners. But the success of high and mid-market disruptors calls for a broader definition of disruptive innovation. Perhaps it is better defined as "innovation that cannot be responded to by incumbents". This definition doesn't lend itself to easy predictions based on the market segment being targeted by new entrants. Analysts and investors must instead do the hard work to determine whether incumbents can respond. They will have a large incentive to do so if new entrants target high-margin products. But incentives do not always guarantee success. If a new entrant is sufficiently differentiated -- whether via underlying technology, geographical reach, distribution method, or network effects -- it can disrupt the market regardless of price. Comments are closed.

|

What this isInformal thoughts on stocks and markets from our CIO, Evan Tindell. Archives

December 2023

Categories |

Telephone813-603-2615

|

|

Disclaimer |