|

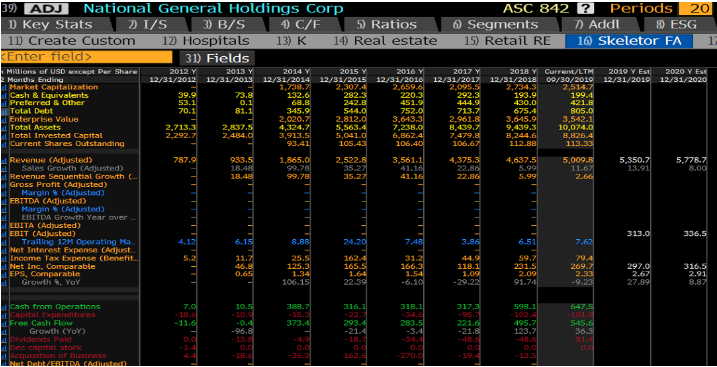

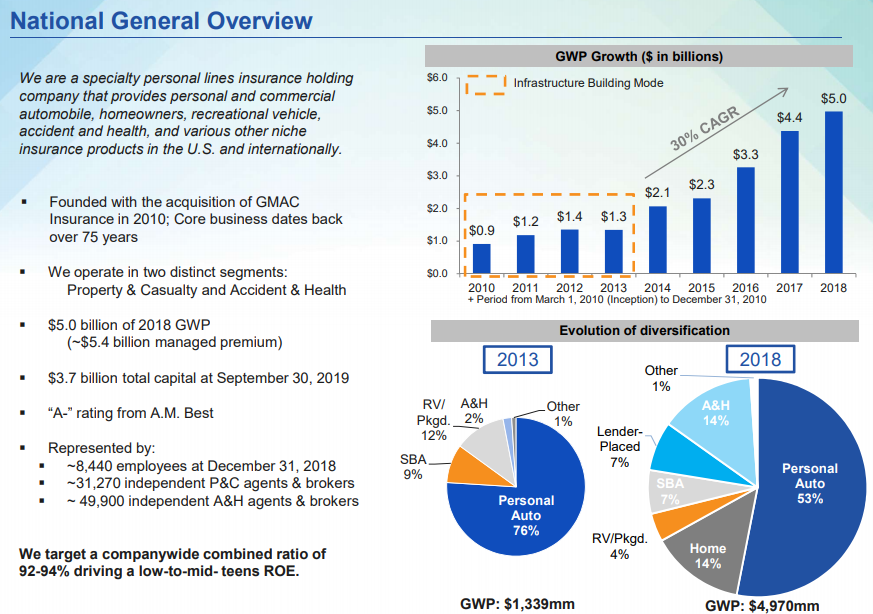

Insurance is a strange business, because unit costs are not known ahead of time and are different for every customer. Sometimes these costs are not fully known for decades, such as when asbestos claims surfaced in the 1970s and resulted in hundreds of billions of dollars in liability for manufacturers and insurance firms. Not only are costs not known ahead of time, but they are different for each customer. In some cases the factors most heavily influencing claims are random. Who can know which coastal town in Texas is more likely to be hit by the eye of a hurricane? For car insurance, though, the customer is in much more control. While there is certainly still lots of randomness to car insurance claims, an aggressive driver has a much different risk profile than a conservative one. Since this factor -- how someone drives -- is both heavily correlated to insurance risk and knowable ahead of time, car insurance companies make a big effort to quantify it. In the early days of auto insurance, this was pretty tough. Insurance companies had to make an educated guess based on age, gender, and driving history (tickets, accidents, insurance claims). Over time, though, insurance companies have gotten more sophisticated at collecting data. One innovation was usage-based insurance and Progressive’s Snapshot system, which monitors a driver's actual driving data and offers a discount to drivers that don’t drive late at night and don’t make a lot of sharp stops. Another innovation was the use of credit history when pricing insurance. What companies found was that customers with poor credit were more likely to generate insurance claims, either because of poor driving or due to fraud. Auto claims generate a plurality of insurance fraud, and this fraud is estimated to cause all drivers to pay $200-300 more in car insurance premium annually. Over time, companies like State Farm and Nationwide learned to decline customers with low credit scores or quote them very high rates. These people still need car insurance, though. What developed was a market for “non-standard” (low credit score, lots of accidents, etc) car insurance. And this became the focus of a small company named National General Holdings Corporation. Motors Insurance National General is not the original name of this company, which was founded as Motors Insurance in 1925. Interestingly, Buffett used the company as an example of the failure of auto companies in insurance during last year’s annual BRK meeting: In one sense, he is not wrong. Motors Insurance did not make much of an impact on GM’s business, despite having a decade head start on Progressive. And yet the company still exists as National General. After going through multiple owners, starting with the sale of 51% of GM’s finance and insurance arm (GMAC) to Cerberus in 2006, National General eventually emerged as a standalone company and IPO’d in 2015. They branched out from merely insuring GM cars long ago, and now sell RV insurance, home insurance, as well as certain forms of medical insurance. Since the IPO, the company has grown substantially, from $1.9b in revenues in 2014 to $5.0b on a T12 basis. They appear to have gained market share across many different lines of P&C insurance, all while maintaining an enviable mid-single-digit underwriting margin (higher than peers). Perhaps the most interesting part of the business is the Accident and Health (“A&H”) product line. In that segment, the company applies their data crunching skills, honed in the non-standard auto business, to price non-standard health insurance policies like short-term medical, cancer/critical illness coverage, and small group stop-loss coverage.

For this type of health coverage, insurers are allowed to use customer data in their pricing, unlike, say, ACA exchange policies. They use all available data points, including pre-existing conditions and credit scores. National General’s familiarity with this kind of multivariate data analysis gives them a leg up on most health insurance companies, which tend to be focused more on reducing the cost of healthcare delivery. This A&H business was started by the company from scratch in 2012 and has benefited from numerous tuck-in acquisitions. The segment now does $700m in earned premiums with impressive underwriting margins of >15% (although the company admits these will go lower over time). Valuation Given the historical growth of NGHC and the interesting market niche they inhabit, you might think they would trade for a decent multiple. You’d be wrong. The company sells for 8.5x 2019 earnings. Most investors think it's because of management. The Karfunkels Brothers Michael and George Karfunkel were born in Hungary in the 1940s and emigrated to Brooklyn as small children, where the family assimilated into the local Orthodox Jewish community. As the boys grew up they started multiple businesses, including a transfer agent called American Stock and Transfer Trust which was bought for $1b in 2008 after being run by the family for 37 years. Today the Karfunkels are in the top 100 wealthiest families in the US, yet are almost unknown outside of their community. Their family fortune currently stands in the single-digit billions, and includes ~40% ownership of National General as well as full ownership of a company called Amtrust Financial. It is the formerly-public Amtrust that has left a bad taste in investors’ mouths. Amtrust Amtrust is a multi-line insurance company, with a focus on worker’s compensation and general liability products for small and medium businesses. Founded in 1998 by the Karfunkels and their son-in-law Barry Zyskind, Amtrust focuses on niche property and casualty insurance coverage, which the Karfunkels felt was underserved by larger insurance companies. They also operate an extended warranty business, primarily for consumer electronics. The company grew quickly, notching $550m in sales by 2007 and $1.7b in sales by 2012. The following two years saw growth accelerate -- partially due to acquisitions -- and Amtrust did $4b in sales and $458m in net income in 2014. The firm’s underwriting margin stayed at a robust 9-10% over this period, and book value per share grew from $15 to $22. The stock price reflected this performance, tripling over three years to $28 per share. And yet, not all market participants thought their reported profit accurately portrayed the company’s financial results. A short seller’s report released in 2013 claimed that the company was improperly accounting for ceded losses to some captive Luxembourg reinsurers (among other issues). John Hempton (and the company) fired back, saying that the firm’s accounting was proper and that the reinsurance agreements -- and their accounting -- were all kosher and in accordance with US GAAP. I have a great respect for Hempton but in this case he appears to have been wrong. While Amtrust always maintained their innocence regarding the specific allegations made by GeoInvesting, in 2017 they revealed some accounting issues and the stock price got hammered. They restated multiple years of earnings, causing declines in past earnings of up to 15%. The company then proceeded to take large “adverse development” writedowns throughout 2017, essentially admitting that their loss reserves for years 2013-2016 were aggressive and true profits were lower than reported. They eventually posted a $700m operating loss for 2017. But even before the final 2017 results could be released, with the stock languishing at $10 per share -- down 60% from late 2015 -- the firm announced the receipt of management buyout offer and the formation of a special committee. The offer was for $12.25 per share. A fight ensued, with Carl Icahn eventually stepping up to ask for a higher price. While making his case, he argued: "AmTrust has been run for the benefit of the Zyskind/Karfunkel families for many, many years. Excessive executive compensation and questionable dividend policies, as well as a web of related party transactions involving family-owned reinsurance companies, office towers and discounted private jet usage, has advantaged the families over the public shareholders for far too long. Now, this proposed going-private transaction is the Zyskind/Karfunkel’s final insult to AmTrust’s public shareholders." Eventually Amtrust went private at $14.75 per share, a number still materially below its peak. Investors in NGHC appear to remember the ordeal. Final Thoughts National General seems to be a well-run business trading at a very cheap, single-digit multiple of earnings. But can we trust the numbers? NGHC says that auto and health insurance are much shorter duration risks than the worker’s compensation liabilities that tripped up Amtrust. And it is true: these are not the type of product lines that result in large adverse developments from prior years. It seems unlikely that NGHC would see its earnings record trashed, as Amtrust did. And yet I am skeptical of any management team that makes major accounting errors and then, instead of correcting their mistakes, rams through a buyout at depressed levels to keep long-term improvements to themselves. To be sure, the individual members of the Karfunkel family that are running NGHC are different than those that bought out Amtrust. But I wouldn't be surprised at all to see similar business practices given the family connection. What are your thoughts: Is NGHC too cheap to ignore? Or are the numbers too good to be true? Comments are closed.

|

What this isInformal thoughts on stocks and markets from our CIO, Evan Tindell. Archives

December 2023

Categories |