|

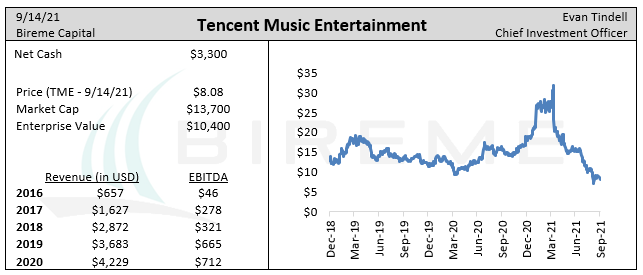

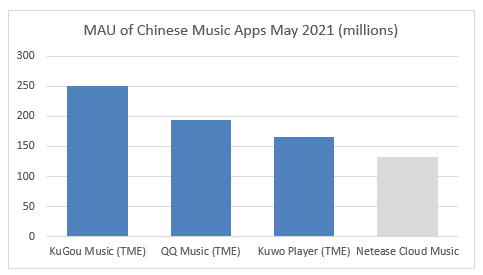

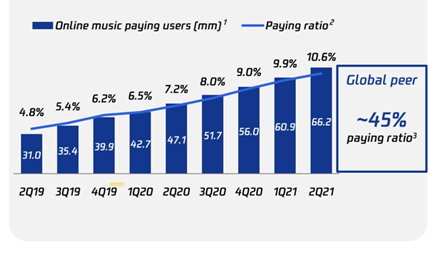

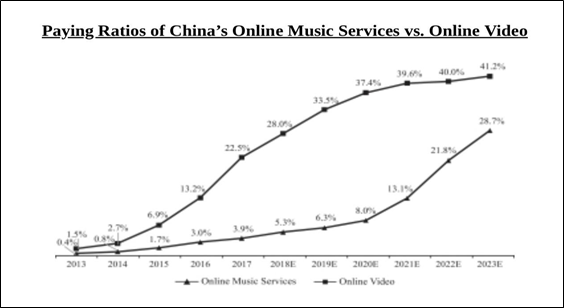

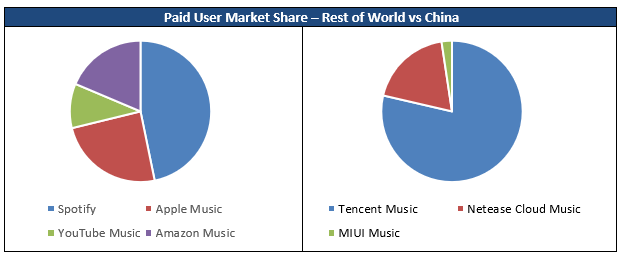

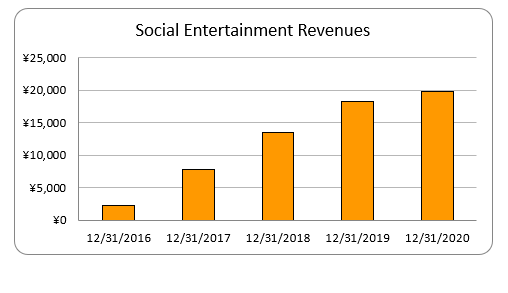

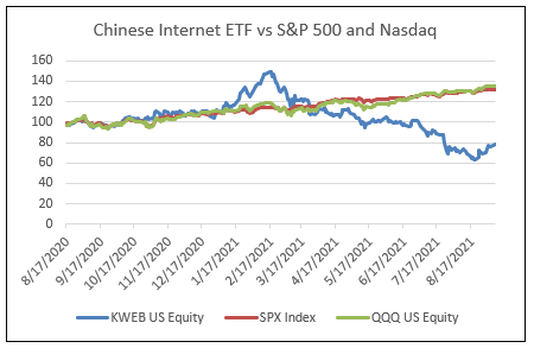

Elevator pitch The history of Tencent Music is one of exponential growth, having increased revenues from 4.4b RMB to 32b RMB over the past 5 years. Today they dominate the online music business in China, with 800m users across multiple platforms. But despite generating nearly $5 billion in revenue, their subscription business has barely begun to scratch the service in terms of monetization. The stock price has collapsed in recent months, first with the liquidation of the Archegos fund -- a major shareholder -- and more recently with the decline of all stocks related to the Chinese internet sector. We think investors worried about the regulation of these companies are falling prey to narrative bias, attributing all actions by the Chinese government to a ruthless power grab. A deeper look reveals a government that is just reining in practices that would’ve been banned in Europe a long time ago. This is exactly the type of investor bias that we seek to exploit in our Fundamental Value strategy. The stock trades at a record low of just 14x ‘20 EBITDA and 17x ’21 EBITDA, a pedestrian valuation for a company that is likely to double its revenues over the next 6-7 years. We think investors buying today, at a stock price of less than $8, will generate an IRR of more than 15% over that time period. Online Music segment Tencent Music has two primary segments: Online Music and Social Entertainment. The “Online Music” segment’s business model will be familiar to western investors: a streamable library of music monetized via subscription and advertising. This is the Spotify model. Three of Tencent’s four apps are specific to this segment, with WeSing focused on karaoke and live performances. The chart below shows how dominant Tencent’s subscription apps were in mid-2021. This business is quite mature in terms of active users, with most of the adult population in China (>600m total) using one of TME’s apps for over an hour per day on average (page 2 of the F-1). Yet this segment still has a massive opportunity to grow revenues, since 89% of users solely use the free tier. This reminds us a bit of Facebook’s mobile app in 2012: hundreds of millions of users, a massive amount of time spent, and very little monetization. It shouldn’t be surprising that the paying rate is low, because historically there was little incentive for a QQ Music or KuGou Music user to upgrade. Downloading more than a certain number of songs was a premium feature, but all QQ’s music could be streamed for free. And unlike Spotify, there is no limit on the number of times a user could “skip” from song to song. But more recently, Tencent Music has been using a paywall to increase their paid user ratio. “Premium” tracks – which you can only stream with a subscription -- now account for about 25% of total listening, moving towards 30% by the end of 2021 as more songs go behind the wall. As a result, paying users have exploded, more than doubling in just two years. We think their paying ratio will move much higher. At a monthly revenue per paying user of 9RMB (about $1.35), the price is quite reasonable for the typical Chinese consumer. We see no reason why the paying ratio won’t increase to 40-50% over time, in line with Spotify, or perhaps even higher (after all, Apple Music has a ~100% paying ratio). If we are correct, this implies a quadrupling of the subscription business (assuming flat ARPU and active users), which today generates 7.2b RMB (or $1.1b USD) in annualized revenue. TME’s 2017 F-1 made a similar projection about the direction of the paying ratio (albeit stopping in 2023), guessing that it would increase to 29% by 2023. So far, they are matching these projections. If TME achieves $4b in revenue in their Online Music segment, we think the enterprise value of the company will be much higher than the $10b or so it is today. For reference, Spotify trades at about 3x sales. But Spotify’s multiple underestimates the potential of the TME subscription business. TME’s bargaining position vis a vis the labels gives it some structural advantages relative to Spotify, and we think this will translate to higher profitability over the long term. In Europe and North America, where Spotify dominates, songs owned by Sony, Warner, and UMG make up more than 70% of listening hours. This is something we mentioned in our Bollore writeup, and it gives the labels tremendous negotiating power: Spotify would simply not have a viable product if a major label pulled out. In China, things are different. The “Big Three” music labels make up a small part of listening hours, which means that dropping any individual label would not dramatically change TME’s offering. From TME’s IPO prospectus: China provides a more conducive environment for Online Music platforms. According to iResearch, in terms of the volume of tracks streamed, the top five labels in China had a combined market share of less than 30% in 2017, while the top five labels globally had a combined market share of approximately 85%. TME can also wield its massive market share in any negotiation. With 600m active users and >60m paying users of their Online Music service, TME is roughly 4x the size of their only significant competitor, Netease Cloud Music, which means that QQ Music, KuGou Music, and Kuwo Player are the primary ways for international labels to reach Chinese consumers. This differs greatly from the dynamic in Europe and North America, where Apple Music, YouTube Music, Amazon Music, and even Pandora are all legitimate competitors to Spotify. This combination of near-guaranteed, long-term revenue growth and likelihood of substantial margins results in an extremely valuable business segment, in our view. Social Entertainment segment The Social Entertainment segment generates revenue via music-related live streaming, from professional concerts to a group of friends having an online karaoke party. Like Amazon’s video game streaming platform Twitch, this business is powered by virtual gifts. This segment operates primarily through an app called WeSing. The growth of this business has been tremendous, from 2b RMB in 2016 to nearly 20b RMB in 2020 (about $3b USD). While they share a large chunk of this revenue with creators — a group which includes some of China’s largest celebrities — the margins are still quite high for this purely-digital platform. In fact, the profitability of the Social Entertainment segment allows TME to generate double-digit consolidated EBITDA margins despite the limited profitability of the nascent Online Music segment. WeSing is seeing increasing competition from apps like Douyin – the Chinese version of TikTok -- but we still think the segment probably grows revenues over the next five to ten years. Why it’s cheap: regulatory fears and the VIE structure Since early 2021, the Chinese Internet segment (a portion of which trades via ADR in the US) is down about 50%. If you look back a full year, it is down about 20% while the S&P is up more than 30%. Said another way, Chinese internet stocks would have to appreciate by about 70% to regain the ground lost to US stocks over the past year. There are probably several reasons for this collapse, but the most cited is regulatory changes. China has made numerous regulatory moves in the last few years, including a flurry this summer, and some have affected publicly traded firms. Some prominent examples:

The CCP says that these regulations are merely designed to enforce existing laws. The five-year legal blueprint released last month, which lays out many of these new rules, is literally called “Outline for the Implementation of Law-Based Government”. However, many commentators have seen the move as an “attack” on powerful tech companies and a bid to re-assert government as the most powerful entity in Chinese society. In some cases, the moves have been characterized as a direct attempt to hurt US investors in those companies. This is the sort of narrative that sends a whole group of stocks down 40-50%, but we think things are not so simple. For one, the idea that the CCP is specifically targeting US investors is a bit silly. Alibaba, which is down more than 50% from its peak, raised $13b USD in Hong Kong in 2019 and trades tens of millions of shares there daily. Tencent Inc, down 30% from its peak, has Hong Kong as its primary listing. If they were targeting US investors, they aren’t doing such a good job. We also think it is overly simplistic to say that the CCP is “trying to assert control”. In fact, many of the regulations that the government is now pursuing are similar to ones already in place in the EU. And US and EU governments have not been shy about enforcing these rules. Here is a list of some of their enforcement actions against the tech sector:

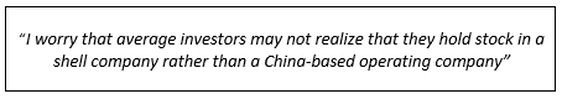

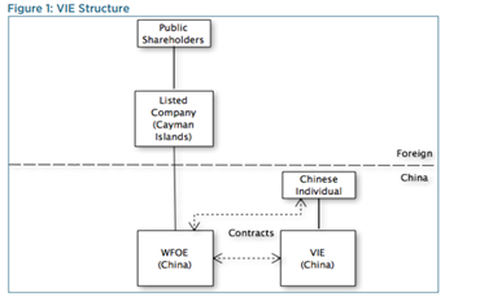

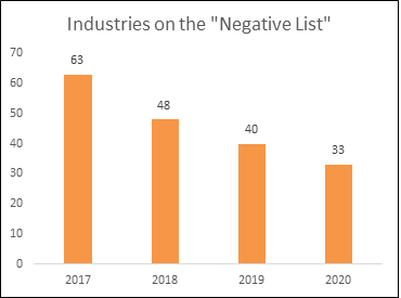

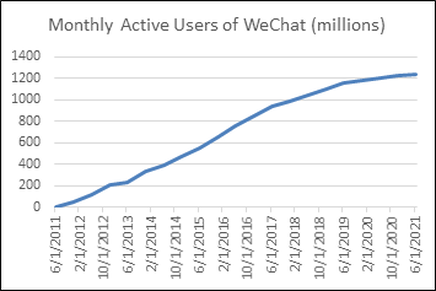

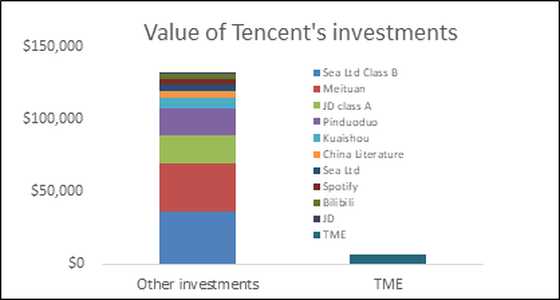

And the list goes on. In our view, the CCP is merely adopting a more Western regulatory stance, albeit in a very abrupt fashion. Investors that think Alibaba or Tencent are worth 50% less due to these changes are succumbing to the narrative fallacy: substituting a story about the big, bad, selfish CCP for a more nuanced – and therefore accurate -- view. We have also spoken with many investors concerned about the corporate structure of these Chinese internet companies. While it is not clear why these concerns would affect stock prices now, given that Chinese ADRs have employed a similar structure for over 20 years, the incoming SEC chair recently sounded off on the potential risks involved: Gensler is not totally wrong: most Chinese ADRs that trade in the US are really Cayman Islands companies. Whether they are truly empty “shells” comes down to your views on something called “variable interest entities” (VIEs), subsidiaries that are controlled by contractual arrangements rather than by normal equity ownership. The purpose of a VIE in China is to avoid foreign ownership restrictions in certain sensitive industries. Typically, the VIE “owner” has a contract in place that grants it all the profits of the VIE, while the shares are nominally held by a Chinese national. This is often combined with a loan agreement, equity pledge, and call option contract which transfers effective ownership of the VIE to the “owner”. VIEs were pioneered during the Nasdaq IPO process of Sina and Sohu in the late 1990s, and hundreds of firms have used them since including Alibaba, JD, and Tencent. The typical structure looks like this: The VIE setup has not been officially sanctioned by the Chinese government. This is not surprising given that the contracts are designed to circumvent the law. While they have not been banned either, the ambiguity around VIEs has led to some spectacular corporate failures. Notable cases include Gigamedia, which involved a key VIE shareholder absconding with the subsidiary’s primary assets, and Alipay – Alibaba’s fast-growing payments business – which Jack Ma attempted to steal by dissolving the related VIE. In the latter case it was not a total loss, as Yahoo and Softbank (large Alibaba shareholders), ultimately negotiated for Alibaba to receive a 33% equity stake in Ant Financial, the parent company of Alipay. For the most part, minority shareholders in VIE-using firms have been sanguine about the risks, relying on the “too big to fail” argument: there is simply too much money – over one trillion USD of market cap -- at stake for the Chinese government to simply rip up this structure. So far, this has held true. The Chinese government has not made an affirmative move towards outlawing these arrangements since they were created in the late 1990s. And as Kerrisdale Capital pointed out, material benefits have accrued to Chinese citizens and the Chinese government as a direct result of the VIE structure: The VIE has been a vital structure for Chinese companies to gain access to foreign capital, bringing a huge amount of economic benefit to China in terms of jobs, taxes, and innovation. The VIE structure has allowed several hundred Chinese companies to raise capital from overseas markets. Many of these companies have become leaders in technology and national champions and are key players in China’s quest to be seen as a global technology leader. The VIE structure supports the broader Chinese objectives of opening its financial markets gradually and reducing restrictions on foreign investments. We thus see little incentive for Chinese regulators to dismantle this structure. While we don’t disagree with this logic, we think there are reasons beyond “too big to fail” to trust VIEs. First there is the stance of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKSE), which has allowed VIEs for years. Investors in these companies include Hongkongers as well as mainland Chinese, the latter having access since 2014 via the Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect. We doubt the CCP wants to permanently impair the investment portfolios of all these people. While the HKSE allows VIEs, they do make various demands regarding the details of the structure. For example, companies must put in place a mechanism to unwind the VIE as soon as the law allows. We see this rule as a positive sign that China’s foreign ownership rules -- at least in the eyes of the HKSE -- may not be permanent. There is evidence for that position, as foreign investment in China has been on a path of liberalization ever since the end of the Cultural Revolution. As the CCP’s own website touts, the 2020 version of the foreign investment restrictions (the “negative list”) are the most liberal yet, and notably jettisoned limits on foreign ownership in the financial services industry. We think it is a matter of time before restrictions are lifted for the value-added telecom industry, making the VIE structures of most Chinese ADRs unnecessary. But the closest thing to full approval of the VIE structure occurred just last year when VIE-user and Segway-brand-owner Ninebot IPO’d on the nascent Shanghai STAR exchange – the first ever mainland VIE IPO. Today, the company sports a market cap of $8b USD, up 200%, indicating that local Chinese investors are not particularly worried about Ninebot’s corporate structure. The CCP leadership was almost certainly consulted on this offering. With the number of industries subject to the negative list declining over time, the HK Exchange’s long-time approval of VIEs, and Ninebot’s IPO, we see the risk of a VIE-related disaster as very low. This gives us the confidence to invest in undervalued Chinese companies, like TME, at the height of investor pessimism. Corporate governance and Tencent Management is important in any business, but it is especially key when you are relying on dubious legal contracts for your ownership. We think Tencent, controlling shareholder of TME, has one of the best management teams in the business. Founded in 1998, Tencent is one of the largest companies in the world, with a market capitalization of about $600b USD. The company was started by Ma Huateng aka “Pony Ma” and four classmates after they saw a presentation about the ICQ messaging platform and decided to build a similar product in China, eventually calling it “QQ”. By 2004 QQ was the largest online communication platform in China. Today their primary chat product is WeChat, a separate messaging app launched in 2011, which has more than 1.2b monthly users worldwide. WeChat is synonymous with online communication in Asia and is the springboard for numerous other Tencent applications, from online gaming to food delivery. The growth of WeChat has been tremendous over the years and its direct link to Tencent Music’s apps is a major reason those platforms have become so popular. Tencent Inc. has delivered massive returns to investors. The Hong Kong shares, under ticker 700 HK, have appreciated from 10 HKD in 2007 to nearly 500 HKD today. In contrast to many Chinese tech companies, they have consistently paid a dividend, growing it from 0.03 HKD in 2008 to 1.6 HKD today. While the trailing yield may be <1%, the T12 dividend amounts to about $1.5 billion USD, a substantial notional amount. Anyone who bought in 2007 is currently getting a double-digit yield on their cost (not to mention the massive capital appreciation). Tencent is renowned for its investment acumen. It has backed many of the most successful Asian technology companies of the past decade, including JD.com, Meituan, Sea Limited, Pinduoduo, and Kuaishou (a TikTok competitor). All told, these stakes were worth over $200b in Q1 2021. We are not worried about the quality of the decision-making process at Tencent. The sheer size of this portfolio – which consists primarily of minority stakes in Chinese tech companies, also gives us some comfort with respect to our investment in TME. Tencent has made a massive bet on the ability of the VIE structure to protect minority shareholders, and we don’t think they are incentivized to try anything tricky at Tencent Music: Tencent is also relatively rare amongst technology firms in that it is not a controlled entity. Unlike most of its competitors – including Baidu, Alibaba, Google, Facebook, and Snapchat -- the firm does not employ a dual-class share structure. In fact, Chairman Ma Huateng only holds about 8.4% of the shares, enough to make him a very rich man but far from a controlling stake. Of course, as founder and long-time CEO, he has considerable sway over the board, but this stems from his successful stewardship of the company rather than the number of shares he holds. The largest shareholder of Tencent is a South African investment firm called Naspers which holds about 30% of shares outstanding.

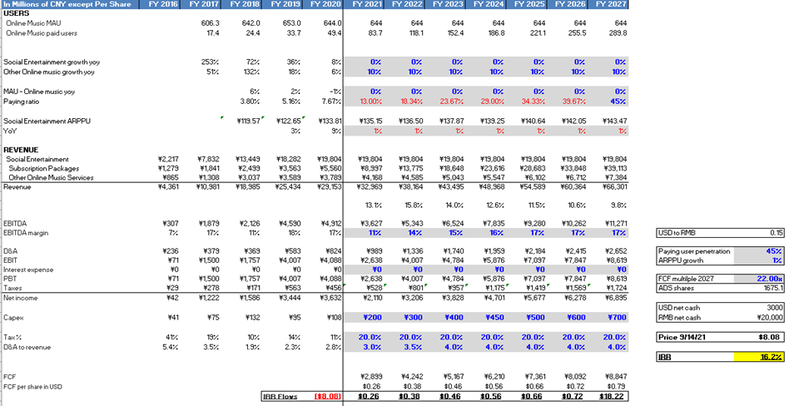

The diversity of voting power at Tencent contrasts markedly with the structure of Alibaba, where founder Jack Ma and his lieutenant Josepha Tsai were able control the company at the time of its IPO via an “inside partnership structure” that removed the ability of shareholders to elect the board. This structure may have contributed to Ma’s theft of majority ownership of Ant Financial, arguably the largest corporate governance failure of all time. Given Tencent’s lack of controlling shareholder, we think a similar disaster at Tencent – and thus, Tencent Music -- is extremely unlikely. Balance sheet, estimates, IRR projection Like its parent company, Tencent Music maintains an extremely conservative balance sheet. As of 6/30/21, the company had about $4b USD in cash and investments and only $800m of debt. This means that while the market capitalization of the company is just over $14b USD, the enterprise value (net of cash and debt) is closer to $11b USD. Given the strength of Tencent management and the cash-rich balance sheet, it is not surprising that they reacted to the cascading share price this spring by announcing a $1b buyback. They executed over $200m in Q1 2021. There is likely to be an increasing amount of cash available for buybacks in the future, as our projections estimate TME will generate about 60b RMB ($9.3b) of revenue and 7b RMB ($1.1b) of profit by 2027, primarily due to growth in the Online Music segment. Here are a few of our key assumptions:

With these assumptions, we think TME grows double digits for each of the next 6 years, generating 79c of FCF by 2027. Assuming a terminal FCF multiple of 22x, we think investors in the stock today will more than double their money, generating a >16% IRR and substantially outperforming the overall market.

Daniel Chase

10/11/2021 09:32:39 am

A very interesting discussion of the risks involved, not just with Tencent but China in general. 15% sounds attractive, but I'm not convinced that it adequately compensates for the unusual risks and ambiguities involved. Comments are closed.

|

What this isInformal thoughts on stocks and markets from our CIO, Evan Tindell. Archives

December 2023

Categories |

Telephone813-603-2615

|

|

Disclaimer |