|

I did two podcasts over the past month talking about our Q4 letter. We discuss my background, poker, statistical value investing, current market conditions, and a few investment ideas. Enjoy!

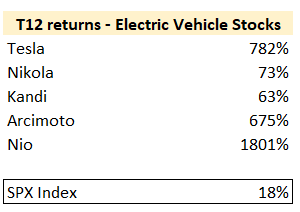

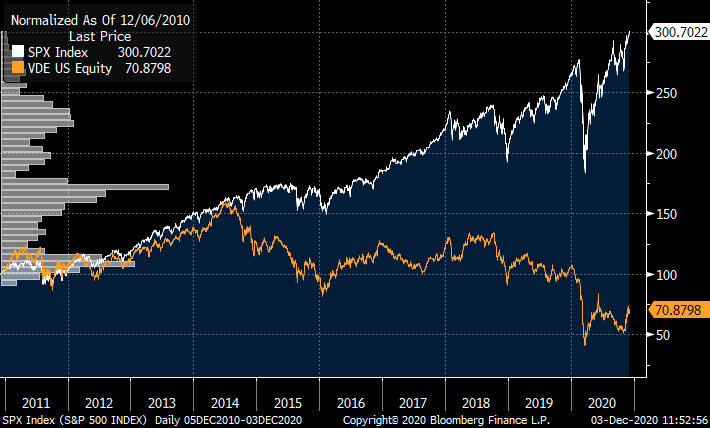

Acquirer's Podcast w Tobias Carlisle This Week in Intelligent Investing w Elliot Turner Enjoy! It is very common for gamblers to learn lessons. It is easy to see why: there is so much data for the gambler to consider. In roulette alone there are all the numbers... are they low numbers? Red numbers? Numbers divisible by three? What color shirt is the dealer wearing? There are so many opportunities to learn lessons if you are looking for them! Almost all of these lessons are nonsense. Rational people understand this because the randomness in a casino is very explicit: an equal-weighted die, a well-spun wheel, or a shuffled deck of cards. For these games, anything except a mathematical analysis of optimal play -- based solely on the rules of the game -- is irrational. It is superstition. In the real world, the lines are more blurred between what is random and what is not. One could even argue there is no such thing as randomness at all. Was the person that took a job at a future unicorn the beneficiary of chance, or just prescient? If you were smart enough -- or perhaps had a computer in your shoe -- couldn’t you predict where the roulette ball would land? Is it lucky that the Pfizer / BioNTech vaccine works so well, or is it the result of decades of scientific research? Cleary there are opportunities in this world to sift through randomness and find truths which can be exploited. At the very least, there are opportunities to tilt the odds in our favor. The world of investing, though, is a particularly difficult place to spot such truths. Yesterday's “truth” may merely be noise. Or, if enough people are aware of it, yesterday’s truth will become today’s random walk. There is still an active debate about whether skill exists at all in investing. I do believe there is skill in investing. As a former poker player, however, I am acutely aware that small sample sizes can be misleading. This applies to investors, strategies, or simple rules of thumb like “sell in May and go away”. And learning too much from small sample sizes is particularly dangerous for bottom-up stock pickers. Some quick math will help us see why. Let’s say you are a fairly concentrated portfolio manager that typically holds 20 positions. If you turn over 5 positions per year that means over a period of 10 years you will own 70 stocks (the 20 you start with and 10 x 5 new ones). If you do a good job, maybe 10-15 of these stocks show losses over your 4-year average holding period. Perhaps 5 of them will suffer large losses of >50%. If you throw in thematic errors of omission like “missing out on the SAAS rally”, you may have ten total mistakes to analyze. Is it possible to learn anything from these ten mistakes? The answer is likely no. There is just too much randomness involved. Unless you can identify an underlying causal factor which is applicable across market cycles, taking lessons from such a small number of cases is a fool’s errand. It leads investors to double down on today’s hot strategies and divest from what is underperforming. If enough market participants invest based on these “lessons”, price movements can become self-fulfilling and move towards extremes. Below is a partial list of market “lessons” that have been learned by investors over the years: 1960s: only invest in the largest fifty companies 1970s: don’t invest in bonds 1990: don’t invest in banks 1999: buy anything tech, stay away from value 2002: don’t buy anything tech 2005: invest only in value stocks, especially banks 2007: commodities and resource stocks are an asset class 2017-today: bitcoin is an asset class 2010-today: valuation doesn’t matter, #neversell, only buy growth stocks Of course, all but the final two “lessons” have proven to be mirages. These mirages are top of mind for me when people on twitter ask what lessons we have learned from our past mistakes. Are people really learning the right lessons from their own small sample size? And further, have the past ten years really been a good teacher, or are all of these *lessons* merely a reflection of larger market trends? On the long side, the lessons being learned are obvious: Always invest in electric vehicle IPOs. Make sure not to pass on Special Purpose Acquisition Companies. You can’t lose money on SAAS stocks. 30x sales is still cheap for a “good business”. And the most frequent lesson of the past decade: never sell based on valuation. The opposite lessons are also being learned: you can’t make money in stocks that don’t grow. There is no such thing as a mediocre company being “too cheap”. Don’t invest in banks, cyclicals, or energy, because “bad” industries should be avoided altogether. The performance of the Vanguard Energy ETF demonstrates how long investors have been trained to avoid bad industries: As we mentioned earlier, these "lessons" can become self-fulfilling, as more and more investors "learn" them. This dynamic can cause trends to stray beyond pure randomness, and even beyond what is warranted by underlying industry dynamics. If they go far enough, they can create opportunities for investors who pay attention to valuation and are willing to look into the future rather than the past. These are the investors that buy 30 year bonds in 1982 or value stocks in 2000. Perhaps the right approach to the "lessons learned" question is to invert it: What lessons are investors learning today that aren’t based on any fundamental truth? In other words, what does the market know for sure that just ain’t so? This is where you will find the real opportunities. Given that Warner Music Group has recently had an IPO, I thought it would be interesting to compare the company to privately held UMG, which we own via Bollore. UMG and Warner, along with Sony, make up the "big three" music labels owning 80-90% of revenue-producing music.

History of Warner Music In 1957, an actor for Warner Brothers movies made a hit song for an independent record company. Sensing a missed opportunity, Warner created Warner Bros. Records in 1958. This served as a platform for numerous acquisitions, including Atlantic Records. Atlantic paved the way for WMG's success, and during the 60s and 70s became the home of hit artists such as Ray Charles, Aretha Franklin, Led Zeppelin, Bette Midler, Neil Young, and Cream. Today, WMG traces its roots back to 1811 via their Chappell and Co subsidiary, which was purchased in 1987. That firm was once called "one of the best publishers" by Beethoven himself. Uniti Group is a weird little company that trades 9x EBITDA and arguably a ~20% free cash flow yield to the equity.

The company owns fiber optic cables and copper wires and leases them to ISPs, mobile wireless providers, and businesses. Comps Owning fiber-optic cables can be a good business. Fundamentally, they are the key asset behind a roughly $70b market in the US - fixed broadband internet (and increasingly important in mobile wireless as well). Once deployed, fiber is costly to compete with: the only real way to do so is to “overbuild” your own fiber. Estimates of the cost to run fiber to one household varies between about $700 for telcos to wire existing customers to $1250 per home for a near-nationwide build-out. Costs are even higher in some rural areas where homes are far apart. Insurance is a strange business, because unit costs are not known ahead of time and are different for every customer. Sometimes these costs are not fully known for decades, such as when asbestos claims surfaced in the 1970s and resulted in hundreds of billions of dollars in liability for manufacturers and insurance firms.

Not only are costs not known ahead of time, but they are different for each customer. In some cases the factors most heavily influencing claims are random. Who can know which coastal town in Texas is more likely to be hit by the eye of a hurricane? For car insurance, though, the customer is in much more control. While there is certainly still lots of randomness to car insurance claims, an aggressive driver has a much different risk profile than a conservative one. Since this factor -- how someone drives -- is both heavily correlated to insurance risk and knowable ahead of time, car insurance companies make a big effort to quantify it. In the early days of auto insurance, this was pretty tough. Insurance companies had to make an educated guess based on age, gender, and driving history (tickets, accidents, insurance claims). Over time, though, insurance companies have gotten more sophisticated at collecting data. Clayton Christensen is an HBS professor that coined the term "disruptive innovation".

The theory His theory states that disruption is made possible by low-end (read: cheap) or new-market footholds. Incumbents have little incentive to match prices with low-end disruptors since it would hurt their margins. This allows the disruptor to gain market share with little direct competition. Eventually, their product improves and becomes "good enough" for a large segment of the market. At this point it may be too late for incumbents to change course. Often the disruptor has developed new manufacturing or distribution methods (with the original goal of lowering costs) that make their strategy harder to imitate for the market leaders. In my view, Christensen's theory focuses too much on price. The number of investment ideas and full-fledged stock writeups in the public domain has got to be at an all-time high. Whether its on Value Investor's Club, SumZero, Seeking Alpha, or simply on twitter, there are probably multiple writeups on the vast majority of publicly traded equities.

I look at all the above. But one of the places I enjoy browsing for ideas the most is in quarterly investor letters. The folks at r/securityanalysis make this process extremely easy by collating a vast array of publicly-available letters. Here is the posting for Q3 if you want to check it out. Below are a few ideas from that post that I thought were interesting. To my wife's chagrin, I'm slightly obsessed with another woman. The other woman is smart, accomplished, and ... 76 years old. Her name is Judy Faulkner. Here are some of her accomplishments:

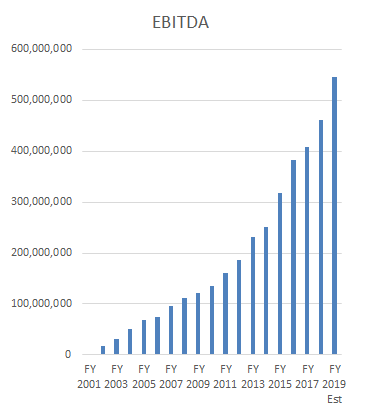

Perhaps now you understand why I think she's so cool. What multiple would you pay for a business with the following EBITDA profile? To help you out a bit, allow me to include a couple more details:

Does 10x EBITDA sound like the right number?

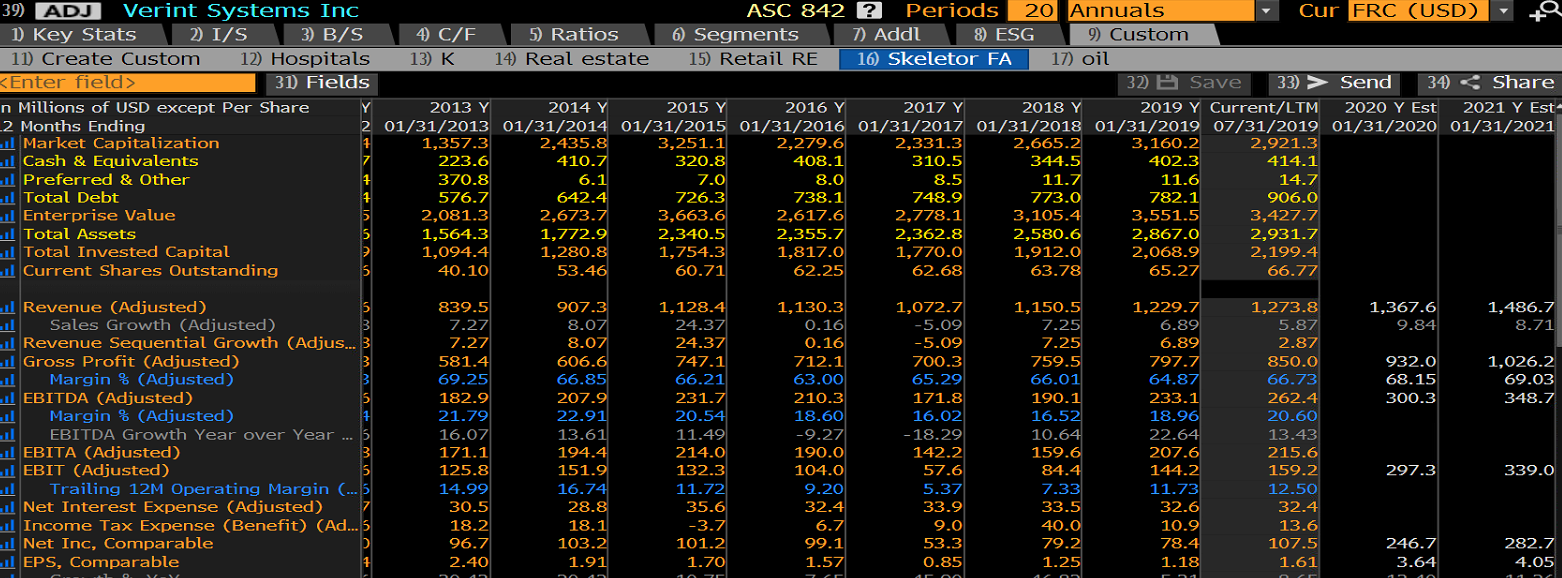

Today's post is on Verint Systems (VRNT), a software company started under Comverse Technology in the 1990s and IPO'd in 2002. I decided to take a look at this company because it's in the software business -- an industry I like -- and it was trading near a 3-year low price. We find that screening for this level of negative sentiment provides good hunting ground for stocks that are affected by cognitive biases. For more background on our cognitive bias framework for finding undervalued stocks, see here. The financials Here's a look at their numbers over the last few years: What is clear at a glance is that this company is not exactly a rocket ship: sales appear to be growing at a mid-single digit rate in recent years and are nearly flat since 2015. Adjusted EBITDA margins are flat at around 20%, lower than many software companies. Shares outstanding are up more than 50% since 2013, probably evidence of the company's looseness with share issuance for acquisitions and employee compensation. |

What this isInformal thoughts on stocks and markets from our CIO, Evan Tindell. Archives

December 2023

Categories |

Telephone813-603-2615

|

|

Disclaimer |